American wine producers have always sought to associate themselves with their European counterparts. We’ve all seen the domestic wineries designed as faux Tuscan villas, and the domestic labels printed with self-styled names that begin with Château or Domaine.

But quietly, over the past three decades, a few American wine regions have gone in another direction. Instead of putting on airs, these groups of quality-minded producers have been drafting laws. And over the past couple of years, this movement has picked up significant momentum.

Examining the EU Model

Wine laws within the European Union set a baseline for quality and veracity that is higher than that of the United States. The appearance of an appellation (AOP, DOP, and so forth) on an EU wine label is a guarantee that all the grapes in that wine came from that geographical designation. By contrast, U.S. federal regulations require only partial truth in labeling—that is, 15 percent of the fruit can be sourced from an appellation other than that stated on the label.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

While it’s relatively rare for a grape variety to appear on a European label—the connection between place and style being so strong there—the use of a varietal designation is a guarantee that at least 85 percent of a wine must be made from the grape variety stated in bold print. In addition, wines from regions that have historically used varietal labeling, such as Alsace, are entirely composed of the advertised grape. (This even goes as far as 100 percent clonal labeling, as in Brunello di Montalcino.) In the U.S., in contrast, a full quarter of the grapes in a varietally labeled wine can be something else entirely.

Regionally, winegrowers’ organizations in Europe exercise legislative oversight at a more granular level than international (EU) and national (AOP, DOP, and so on) agencies are able to do, with far more authority than any U.S. regional wine board wields. We’ve all studied those bullet points covering the months and years of oak aging that differentiate a Crianza from a Reserva from a Gran Reserva, for example; even outside of the cellar, growers must meet density, training, and fruit load requirements in order for a wine to earn that coveted Rioja seal.

In comparison, an American Viticultural Area (AVA) committee would never require winemakers here in the land of the free to follow strict rules in the vineyard or the cellar … or would it?

A couple of recent headline-grabbing events in Oregon have sparked conversations in wine circles about the laissez-faire American attitude toward veracity in labeling and prompted a reconsideration of the value of cellar oversight. And these are merely the most recent developments in a three-decade-long movement that has made at least a couple of our AVAs look decidedly European. Will the remainder of American wine country follow suit?

Calling in the Feds

Two parallel developments from Oregon are in the sights of industry insiders right now. On the national level, a group of six U.S. senators and representatives have demanded a federal investigation of the California winery Copper Cane. Complaints filed by the Oregon Winegrowers Association claim that Copper Cane has violated TTB (Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau) codes by misrepresenting the provenance of some of its wines.

One Copper Cane brand, Elouan, is labeled “Oregon Pinot Noir,” with a map showing the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue AVAs and the legend “The Coastal Standard. Purely Oregon, Always Coastal.” None of these appellations are coastal, and this “Purely Oregon” wine is, as the label states, “vinted and bottled” in Rutherford, California. Another Copper Cane brand, The Willametter Journal, implies Willamette Valley AVA status through its suggestive proprietary name. Additional verbiage on the front of the bottle states that the wine is sourced from “the Willamette region of Oregon’s coastal range,” while the back label describes the wine as the product of the “Territory of Oregon.”

TTB rules allow for a wine label to be printed with the name of an AVA only if, as stated above, 85 percent of the grapes in the bottle were grown within that appellation and the wine was “fully finished within the state … within which the labeled viticultural area is located.” Although the code does include provisions for out-of-state manipulations and corrections to finished wines, Copper Cane’s owner, Joe Wagner, has stated publicly that his Oregon wines are entirely vinified in California.

In late November, news broke that the TTB had, in fact, responded to months of complaints from Oregon winegrowers and ordered Copper Cane to surrender its misleading labels. However, this directive did not include inventory already in distribution.

But while the Copper Cane controversy provoked a response from the agency, the issue was already on the TTB’s radar. In 2016, in response to input from winemakers and legislators from Oregon, Washington, and California about deceptive labeling, the TTB proposed revisions to wine-labeling requirements that will enhance its authority to crack down on wineries that bend labeling rules by taking advantage of exemptions to Certificate of Label Approval (COLA) requirements.

Given the current deregulatory atmosphere in Washington, it’s difficult to guess when these in-limbo proposed rule changes might be enacted. But Congress stepped in this year to give weight to the issue. In March, U.S. Representatives Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) and Lee Zeldin (R-NY) introduced a Congressional resolution recognizing the uniqueness and value of American Viticultural Areas. Then, in September, the Senate passed a similar resolution, sponsored by Senators Roy Blunt (R-MO) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR).

At this point, free-market adherents may be wondering why, just as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is being dismantled, the wine industry and the TTB are moving toward European-style protectionism.

Doubling Down on Willamette

Meanwhile, on the regional and state level, the Willamette Valley Wineries Association is proposing to roll out the most stringent labeling rules in the U.S.—more stringent than Oregon State’s already-strict regulations. Oregon currently requires that 95 percent of a wine must be from the AVA on its label, and 90 percent must be of the stated variety (with some obscure exceptions). The WVWA proposal would compel producers of Willamette Valley-designated wines to source their fruit entirely from the Willamette Valley appellation, with varietally designated bottles consisting entirely of the named grape variety.

After numerous discussions and town hall meetings, the winemakers of the Willamette Valley have mostly agreed with the tightening of requirements. Mike McNally, a co-owner of Fairsing Vineyard in Yamhill, Oregon, and the vice chair of the WVWA, says that he expects to see final legislation within a year. And while a state doesn’t have the enforcement power of the TTB, “we feel there is gravitas to walking into a winery and saying, ‘Do you realize you are in violation of an Oregon law?’” observes McNally, who adds, “They will care about the press they’ll get if their license is revoked.”

If federal and state oversight fall through, though, it’s worth noting that litigious-minded producers—whether in Oregon or elsewhere in the U.S.—also have the option to take the law into their own hands to enforce truth in labeling. This is thanks to the Lanham Act, which Congress passed in 1946 to expand on the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. When one winery sues another because its name is too similar, it’s referencing the Lanham Act in its claim of trademark infringement. In 2014 the pomegranate juice company Pom Wonderful caused the court to expand its interpretation of the Lanham Act to include false advertising.

Coca-Cola was marketing a Minute Maid juice product at the time as Pomegranate Blueberry Juice, when in fact the beverage contained only 0.3 percent pomegranate and 0.2 percent blueberry juice. Pom Wonderful, which makes an 85 percent pomegranate and 15 percent blueberry juice, called foul. The case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled that Pom Wonderful had the right to sue—which opened the door for one winery to sue another for deceptive labeling without waiting for enforcement on the federal or state level.

“For many decades it seemed like we had to wait around for the government to do something in the case of misleading marketing,” says Robert C. Lehrman, principal attorney at Lehrman Beverage Law in the D.C.-beltway suburb of Oakton, Virginia. “The Pom case reminds us that under the Lanham Act, one company or set of private interests can go after another company to the extent they can show that the labels are misleading and it hurts the complainants.”

Copper Cane’s Joe Wagner looks to have done just that, but not in a protectionist manner. When Jim Bernau, the founder of Willamette Valley Vineyards, personally challenged Wagner on his misleading use of the Willamette name on his labels, Wagner responded by filing suit to cancel Bernau’s trademarks, apparently in retribution. Willamette Valley Vineyards was founded in 1983; the Willamette Valley AVA was established in 1984.

Following in Napa’s Footsteps

Of course, a civil lawsuit is a very American way to solve a problem, and in the case just cited, it seems to have been wielded as a form of suppression. Europeans go the regulatory route. And a few U.S. wine regions have been following this latter path for about the past three decades.

Oregon’s Willamette Valley may be in the spotlight right now, but California’s Napa Valley Vintners Association was the first in the U.S. to legally protect its appellation name. As far back as 1990, the NVVA successfully lobbied for state legislation requiring conjunctive labeling—that is, a wine label printed with a Napa Valley subappellation, such as Mount Veeder or Calistoga, must also include the “Napa Valley” designation. Paso Robles, Sonoma County, and Monterey have since passed similar laws, and a conjunctive labeling provision is part of the pending Willamette Valley legislation in Oregon. (Interestingly, the Napa Valley was ahead of Europe on this point. Burgundy, for example, did not require conjunctive labeling until 2002. Look closely at that post-2002 bottle of Montrachet and you’ll see in fine print the words Grand Vin de Bourgogne.)

In 2000 the NVVA successfully sponsored California legislation that required truth in labeling for any wine marketed with the Napa Valley appellation … whereupon Bronco Wine Co. filed a lawsuit challenging it. After five years in the court system, however, the law was upheld by the state supreme court.

Then, in July 2005, the Napa Valley made protection of origin an international issue, when it hosted a convention of eight regional wine associations that were invited to sign the Joint Declaration to Protect Wine Place Names & Origin. The group consisted of Champagne, Oporto, and Jerez in Europe, and the Napa, Willamette, and Walla Walla Valleys in the U.S., as well as the states of Oregon and Washington. The organization, now known as the Wine Origins Alliance, today has 24 members throughout the world, including Burgundy, Chianti Classico, and Champagne—European regions that continue to see their names appropriated by California jug-wine producers.

The final feather in the NVVA’s cap (or, perhaps, beret?) came in 2007, when the Napa Valley appellation attained Geographic Indication status from the European Union, never mind the 5,500 miles separating Napa from Nantes. And in 2018, with Brexit looming, the Napa Valley trademarked its own name in both the U.S. and the U.K.

The one line the Napa Valley has not yet crossed, however, is designating certain single vineyards as superior to others—that is, it has not attempted to establish crus, in the French tradition. In a nation where money trumps tradition, one can only imagine the ruckus that would be raised by a governing body declaring one vineyard superior to another, especially if the owner of the “inferior” vineyard paid more per acre for the land. (Mike McNally, the vice chair of the WVWA, tells me that cru designations were part of the initial brainstorming phase for the Willamette Valley’s proposed legislation, but the idea was immediately scrapped.)

Advocating for Global Accountability

There’s irony in these American crackdowns on the misleading use of place names on wine labels, given our flippant former attitude toward European appellations of origin. We notice the pain that misleading labeling inflicts, apparently, only when we feel it ourselves.

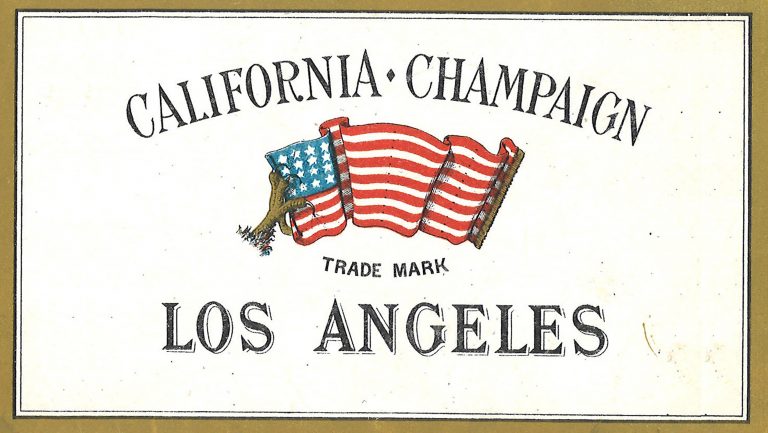

It could be argued that Americans were actually the instigators of Europe’s far-reaching label laws. Take the example of Champagne: As far back as 1839, according to author Brian McGinty, American sparkling wines were being referred to casually as champagne, and “California Champagne” has been a thing ever since.

By 1905, the French federal government had begun to take action to guarantee the origin of its agricultural goods, passing a law that year that allowed for the delimitation of regions renowned for particular types of products. Subsequent legislation, in 1919 and 1935, established the Institut National des Appellations d’Origine (INAO, now known as the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité) and protected geographically defined regions noted for their production of fine wines and spirits.

The next step was to broaden the AOC concept internationally. The Lisbon Agreement of 1958 (an improvement on the Madrid Agreement of 1891) protected the integrity of appellations of origin; it has been amended twice and signed by 28 member nations—the U.S. being a notable exception. The only wine region that seemed to be aware of the problem over the ensuing decades was Oregon, which passed a statute in 1977 forbidding “semi-generic designations of geographical significance”—evidence of an awareness that appropriated place names can reflect poorly on a region.

The World Trade Organization got involved in 1996, when it brokered the TRIPS agreement between 158 entities, including the U.S. The agreement gave member parties the legal means to protect the integrity of their own geographical origins but did not dissuade American wine producers from appropriating protected European regional names.

It was not until 2006 that the U.S. signed the Agreement Between the United States and the European Community on Trade in Wine. Yet even this document grandfathered in the big California wineries that had been using terms like “Hearty Burgundy,” “California Chianti,” and yes, “California Champagne” on their labels. (In fact, if such a winery changes hands, the new owner can continue to use the misleading place names on the winery’s labels.)

Jennifer Hall, the director of the Champagne Bureau, USA, is remarkably diplomatic when I ask her how frustrated the Champenoise must be with Americans for continuing to misuse their name, despite their decades of tireless advocacy. “It takes time for the law to catch up with the industry,” Hall says. “Champagne has been around for hundreds of years. The way we produce our wine, we are very patient with it: Vintage-dated Champagne, for example, does not come to market until at least three years after the vintage.”

And yet … hasn’t enough time gone by? Champagne’s boundaries were first delimited in 1908; Champagne was one of the first regions to be granted AOC protection, in 1936. While U.S. wine regions are rushing to protect their own names, they’re still appropriating others.

Hall believes that the current American trend toward increased regulation in wine labeling is part of a larger overall change in consumer ideology, which will ultimately drive accountability in a way that slow-moving legislation can’t. “There has been a big shift in the way Americans approach the products that they buy,” she says. “We want to know more about the product we are consuming. We want to hear the story behind how something was made. In Europe, regional specificity has always been inherent. There are now 242 AVAs in the U.S. Every single state has an AVA. People want to go to wine country and see what is being made there.”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Katherine Cole is the author of four books on wine, including Rosé All Day. She is also the executive producer and host of The Four Top, a James Beard Award–winning food-and-beverage podcast on NPR One. She is currently working on a fifth book, Sparkling Wine Anytime (Abrams), to be published in Fall 2020.