We’ve all heard of wine prodigies—those few who had a preternatural talent for blind tasting at an early age and who can rattle off vintages, villages, and producers as though they’re walking around with a computer chip in their brains.

And then there’s Andy Fortgang, who was, and is, a different sort of prodigy.

Back in the mid-1990s, before the advent of Food Network child stars, and at an age when most kids are goofing around on skateboards and dreaming of their first date, Fortgang, a baby-faced teen, was already performing like a pro in one of the nation’s top restaurants.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

The kid had drive. He channeled that drive into hospitality, and he’s never let up. Today, Fortgang’s peers, mentors, and former trainees describe him as one of the most serious, dedicated, and competent wine and restaurant professionals in the business.

Sweet and Savory 16

Fortgang grew up in New York City, the child of two busy attorneys. One evening, when he was 14, he asked his mother if she would make linguine with peppers and sausages for dinner despite the fact that she had planned something else. Says Fortgang, with a smile, “Her verbatim response might not be printable.”

That night, Fortgang made his own dinner, and he realized that he had a knack for cooking. Soon he was following the dining business in the same way his peers were following the Knicks, the Giants, and the Mets, rushing home to catch the early food programming on PBS, the Discovery Channel, and the then-nascent Food Network.

The boy’s big break came when his mother, Brauna—who had by then forgiven him for treating her like a short-order cook—got into a casual conversation with an acquaintance who had a friend whose brother was a chef. Hearing about the boy’s obsession with restaurants, the acquaintance offered to make an introduction. “My mom figured nothing would come of such a tenuous connection,” Fortgang says. “[But] then, a couple of weeks later, the phone rang and it was Tom Colicchio. He said, ‘Come on in!’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, Gramercy Tavern? I’m curious about fancy food; I don’t want to work at a bar.’”

Once he realized that Colicchio was the executive chef at one of the nation’s finest restaurants, Fortgang accepted the offer. “It was the coolest thing ever,” he recalls of that first night at Gramercy Tavern. “At the end of the night, I said, ‘Hey, can I come back?’ … I went back once a week until, finally, they offered me a summer job.”

If Fortgang was intimidated at all, he didn’t show it. “He had this bordering-on-cocky confidence, which you would have to have at the age of 16 to be on the line among a bunch of crusty grown-ups,” recalls Juliette Pope, the portfolio manager for Louis/Dressner Selections at David Bowler Wine. Like Fortgang, Pope started her career in the kitchen at Gramercy Tavern before transitioning to wine and directing the restaurant’s beverage program for a decade. The two have remained friends for more than 20 years. “He can be gentle and soft-spoken,” Pope says, “but there is this iron core of confidence to him that was always there.”

Fortgang went on to spend his high school and college summers and vacations in the Gramercy Tavern kitchen—that is, when he wasn’t staging at Aureole and Jean-Georges.

But his parents were skeptical about the idea of their son skipping college and going straight to culinary school. The teenager also began to realize that he was more drawn to the front of the house than the back, so he enrolled in Cornell University’s hospitality program for undergraduates. There he learned the business side of running a restaurant—accounting, finance, facilities management, real estate—while simultaneously soaking up the Ivy League liberal arts education and reveling in Professor Stephen Mutkoski’s wine instruction.

Learning to Lead

In 2001, Fortgang graduated and returned to Gramercy Tavern as manager, directing a staff of professionals who were in some cases twice his age. “Until the day I left, it was always like, ‘Who the fuck is this punk-ass kid?’” recalls Paul Grieco, the owner of Terroir wine bar in New York. “It was one of the most incredible places to work … As long as you had an enthusiasm for learning, you could thrive in that environment. Andy brought that youthful zeal coupled with a solid backbone of education that changed some of our internal dynamics.”

For his own part, Grieco, who was the restaurant’s beverage director at the time, influenced Fortgang’s developing wine philosophy. “The biggest thing I learned from Paul, that’s largely lacking in the wine world,” Fortgang says, “is a complete openness to anything that’s good. He would search out all of these interesting finds from Europe—these edgy producers—but there was never any backhanded indictment of the quality of classic wines.”

As he became a leader himself, Fortgang says he learned from Grieco to listen compassionately, without judgment, and guide students toward discovery rather than teaching from the top down. “At the same time,” Fortgang adds, “one thread that successful leaders I have worked for have in common is not being shy about telling people respectfully and politely when they are wrong.”

Today, Fortgang’s past and present trainees describe him as a skilled communicator, empathetic while also direct. As one admiring former acolyte puts it, “He’s patient, but exacting.” His trainees also describe him as the guy who is the first to arrive and the last to leave—the guy who, dressed for dinner service, takes it upon himself to plunge the clogged toilet so that his employees don’t have to.

Fortgang says he picked up this work ethic at Gramercy Tavern, back when he was so much younger than the rest of the staff that he felt he had to prove himself. “I’ve always been of the mind-set that if you work as hard as you can, you will earn everyone’s respect,” he says. “So I didn’t go around telling people to bus their tables or get their wine order in faster. I would just take care of these things myself if they didn’t get to them.”

Embracing Wine

After two and a half years of managing, Fortgang decided to leave to pursue his growing interest in wine, fueled by Grieco’s training as well as his own direction of the cheese program at Gramercy Tavern. (“Selecting cheeses for a list,” says Fortgang, “got me thinking, What is it that’s making this yellow circle larger than the sum of its parts? And what makes this 750 ml bottle of liquid bigger than ‘fermented juice’?”)

In what he thought was a temporary stop, Fortgang found himself reunited with Colicchio—who had left Gramercy Tavern to open Craft in 2001—covering vacant manager and wine director positions while interviewing for a beverage director job at another prominent restaurant. But Colicchio had other ideas and persuaded Fortgang to stay on, eventually promoting him to the beverage director role for his entire restaurant group.

But first, Colicchio sent the 25-year-old to Las Vegas for six weeks to get a crash course from Heather Branch, who at the time was the beverage director at Craftsteak, managing a massive program. Fortgang’s wine knowledge wasn’t comprehensive, but his managerial skills were top-notch, and he had determined that “the job of being a wine director is more mechanic and administrative assistant than anything else.”

On his return to New York, Fortgang discovered that he possessed a secret resource: “As the buyer for one of the better restaurant accounts in New York,” he says, “I had all the best, most knowledgeable senior reps—people who are now portfolio managers—calling on me. I learned so much from those people. When people ask me how I learned about wine, I say, ‘In a way that is not easy to replicate. On any given Tuesday over the past 14 years, I’ve tasted 40 new wines.’”

Today, Fortgang continues to view sales calls as learning opportunities, asking his team members to sit in on tastings. “It’s a way to really build that wide breadth of knowledge, where you’re not just deeply into one thing,” he says. And he continues to practice what he learned from Grieco: “Tasting wine with the staff every day, having classes, promoting the idea that everyone can be the sommelier. My job is to prepare the staff well enough that 9 out of 10 don’t need me. Because there is only one of me.”

A decade after his first foray into the business, Fortgang was still the kid in the room. “Nowadays, it’s not that unusual to have a young wine director,” says Hayden Felice, the wine director at Acme Hospitality in Santa Barbara, California. “But back in 2003, only the top restaurants had wine directors.” Felice, who assisted Fortgang at Craft between 2003 and 2005, reflects, “He was young, and he looked younger. But he still comported himself with dignity, respect, and maturity.”

Nikki Ledbetter, the beverage manager at Upland in New York City, worked for Fortgang at Craft between 2003 and 2006, eventually taking over the director job after Fortgang left. “I remember him imparting some sage advice to me as a young person in the wine world,” she says. “[He said] to never let yourself be steamrolled or bullied, to always have a clear sense of your own palate, and to always work with integrity.” Ledbetter also credits Fortgang with instilling in her a tradition that has helped with her studies toward her MS certification—opening a bottle off the wine list during lineup every day for the entire staff to taste and discuss.

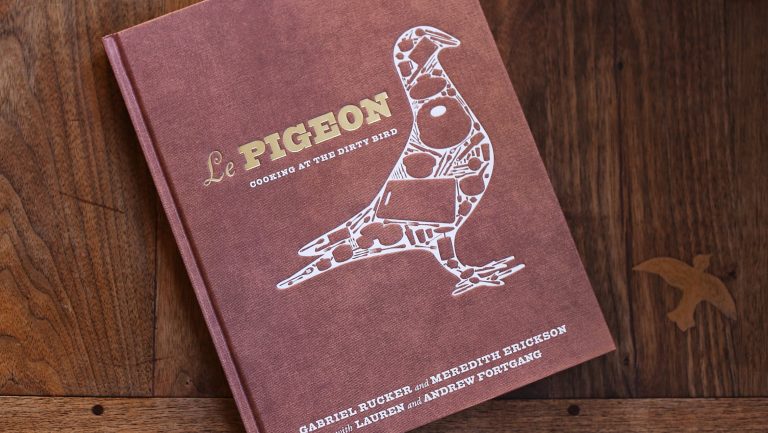

By 2007, Fortgang had married Lauren Dawson, the pastry chef at Hearth (their wedding was featured in the New York Times), and the two were looking to settle down somewhere new. While in Portland, Oregon, interviewing for a position with Bruce Carey Restaurants, Fortgang and Dawson ate at an odd little hole-in-the wall on East Burnside Street called Le Pigeon. The place may have been a bit threadbare at the time, but “it was a really inspiring meal,” Fortgang recalls. “We were both bowled over.” Soon afterward, Fortgang saw a Craigslist posting for an opening for a manager at Le Pigeon and applied. He was offered both jobs.

After much deliberation, Fortgang signed on with the riskier prospect, Le Pigeon. Within a year, he was a 29-year-old co-owner and partner, and Gabriel Rucker, who was still just 27, had been named a Best New Chef by Food & Wine magazine. The partners opened a downtown bistro, Little Bird, in December 2010, and a more casual wine bar, Canard, in April of this year. (Dawson oversaw pastries for the restaurants until the couple’s second child was born—they have a daughter, Dora, who is 6, and a 4-year-old son, Theo.)

Taking Flight in Portland

It’s been a decade since Le Pigeon’s first of many James Beard Award nominations (and later, awards). And—as evidenced by this article—team Fortgang and Rucker continue to attract national media attention. Canard was named the Oregonian’s Restaurant of the Year and one of Eater’s 18 Best New Restaurants in America just a few months after it opened. And Fortgang was recently nominated by Wine Enthusiast magazine as Sommelier/Wine Director of the Year.

Over the years, Fortgang has overseen the management of all three restaurants, while guiding the wine lists. (Today he acts as wine director at Le Pigeon and Canard, while Sergio Licea handles Little Bird.) If there’s any theme that unites the lists, it’s a deep respect for France, but Fortgang “doesn’t chase trends and doesn’t ‘do favors,’” as one former trainee puts it.

Brianne Day, who waited tables for Le Pigeon and Little Bird while she was working toward launching her own wine label, Day Wines, remembers bottle-centric “family meals” at which Fortgang would educate the staff but then ask everyone on the team to engage and improvise, sharing their personal food-pairing ideas with the group. “I think it was a beneficial way of getting the staff thinking about how to best utilize the wine list and feel confident about suggesting a wine,” Day says. “I saw it as a personal challenge.” Similarly, diners at Fortgang’s restaurants describe his approach as collaborative: He listens with the assumption that the customer is curious and intelligent, they say, gently guiding them toward decisions like a seasoned diplomat.

Each wine list is tailored to the venue and exceptional in its own way. Le Pigeon’s wine program, Fortgang says, “is about the food, with wine supporting it.” He edits constantly, limiting himself to both sides of an 8.5-by-14-inch page, cycling wines on and off with the changing menu and seasons. “We don’t want people getting lost in the list,” he says, “and not being with their dining companions.” At Little Bird, the offerings are nearly all French, with a slight nod to Oregon and the West Coast. (Fortgang feels that his diehard local clientele get enough local wines as it is, and that they come to his restaurants to explore Europe.)

One notable exception is Belle Oiseau, an Alsatian Edelzwicker-style white blend Fortgang commissioned local winemakers Brian and Jill O’Donnell, of Belle Pente, to produce as Little Bird’s house white in 2010. While the blend has changed slightly from year to year, it’s made of Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris, and Muscat, and it’s done so well that the winery now sources fruit from other vineyards and bottles and sells it directly to fans.

Canard, the final restaurant in the trinity, was designed to be a playground for enophiles. By keeping food and labor costs down, maximizing efficiency, and opting for low-cost “Parisian wine bar” touches like paper napkins, Fortgang offers rare bottles (or as he describes them, “fun,” “cool,” and “collectible”) at minimal markups. At the high end, a 2013 Mugnier Les Amoureuses Chambolle-Musigny, for example, won’t look like a bargain to the untrained eye, but in fact it’s an absolute steal at $475. At the lower end, under the header Downtown Burgundian, one can find a 2016 Domaine Vessigaud Mâcon-Fuissé for $40.

“I’m not saying we’re doing some great public service,” Fortgang says, “but we are putting some bottles in reach that are normally out of reach for many.”

Fortgang’s lists, while they tend toward European classics, nimbly balance highbrow sophistication with a lack of pretension, in keeping with the vibe at his hot spots, which—for all their international acclaim—are admittedly a little rough around the edges. After all, Fortgang is a New Yorker who moved across the country to buy into a restaurant named after a dirty bird, as the Le Pigeon cookbook subtitle so aptly puts it.

Diners sit elbow-to-elbow with their neighbors in the sardine-can-sized Le Pigeon. Little Bird, while spacious and handsome, is located at the seedy edge of Portland’s downtown. And Canard, next to Le Pigeon at the urban west end of East Burnside Street, delivers its deals on very fine wines against the backdrop of a low-key decor, with old-fashioned bentwood chairs and barstools—a marked contrast to the chic spots just up the street, such as Tusk.

“There’s no pretension,” observes Sean O’Connor, a partner and the director of operations at a forthcoming Icelandic Kex restaurant and hostel in Portland. “There’s no hipster irony. I don’t think Andy knows what a hipster is … Whether it’s a $3 Coors Banquet beer or a $300 bottle of Grand Cru Burgundy, you can get both at Le Pigeon, and your choice, as a guest of the restaurant, will be treated with the same amount of respect. No matter the acclaim, no matter how far out the reservations are booked, there is a way for a guest to be part of the communal experience that is dining at Pigeon, at any price point they’re comfortable with.”

O’Connor, a Le Pigeon and Little Bird alum who credits Fortgang with shaping his own career, adds, “There is no other beverage director in this city who works on the level Andy does. He’s modest, he doesn’t brag, but he is, in reality, the best sommelier in the city … He doesn’t need thousands of Instagram followers or a PR strategy to acknowledge that he’s doing a killer job. The work—and the press he gets—speaks for itself.”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Katherine Cole is the author of four books on wine, including Rosé All Day. She is also the executive producer and host of The Four Top, a James Beard Award–winning food-and-beverage podcast on NPR One. She is currently working on a fifth book, Sparkling Wine Anytime (Abrams), to be published in Fall 2020.