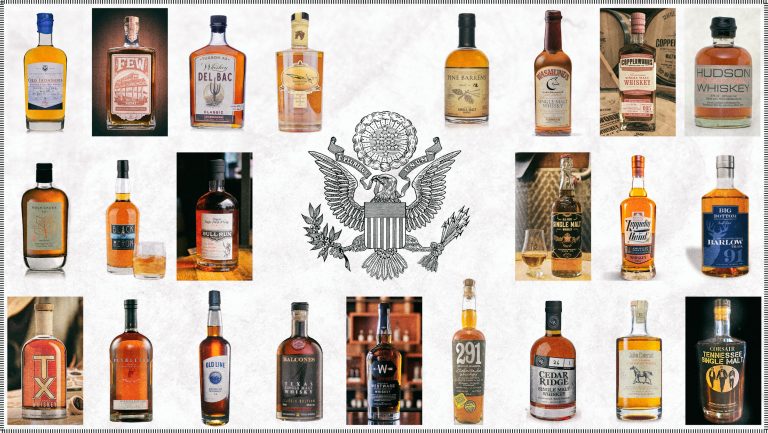

Prepare for the deluge. American single malt whiskey has gone from curiosity to near-ubiquity in the past decade. “We’ve got 100 distilleries now making single malts, and in 10 years it’s going to be 500,” says Christian Krogstad, the founder and master distiller of Westward Whiskey in Portland, Oregon, and the producer of Westward American single malt.

When only a handful of U.S. producers were making single malts—Steve McCarthy, at Clear Creek Distillery in Portland, was the first, in 1993—few consumers paid attention to the differences between one single malt and another. It was enough to distinguish this new category from American bourbons and ryes.

But with store shelves starting to sag under the weight of new entries into the domestic single malt category, the question arises of how producers might classify variations of American malts to make the category more accessible and understandable. “There will be some absolutely clear evolutions of what ‘American single malt’ means,” says Jeffrey Baker, the owner of Hillrock Estate Distillery in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Imitating Scottish Regional Classifications

Given that some American producers of single malts are following traditions rooted in Scotland, it’s not unreasonable to look abroad for inspiration. Scottish single malts are typically classified by the regions in which they’re made: Highlands, Lowlands, Speyside, Islay, and Campbeltown. Each region has historically produced whisky with a recognizable, individual taste profile, so consumers know, roughly, what they’re buying when they try a new brand.

Would that work in the United States? Should consumers be guided to distinguish a Northwest single malt from one made in the Southwest or the Midwest? “I think there has been a drive and some interest in trying to categorize them by region,” says Krogstad. “But I think that’s wrongheaded.” After all, he notes, depending on the production methods or the type of still used, a single malt made in Washington State may have a taste profile that has more in common with one made in Virginia than one made in Oregon.

Other single malt producers tend to agree. “Going regional is certainly attractive,” says Gareth Moore, the CEO of Virginia Distillery Co. in Lovingston, Virginia. “People are attached to a region. But without 100-plus years of history, I don’t think we’re going to have the benefit of [being able to break] it down regionally.”

Colin Keegan, the founder of Santa Fe Spirits in Santa Fe, New Mexico, concurs, saying that it makes little sense to chase after a history that doesn’t exist. “Scotland has its regions,” he says, “but they occurred naturally and organically. People used what they had—it was more expensive to transport than to grow locally.” Over time, that state of affairs has been reversed, both in Scotland and beyond, and now transporting ingredients often makes more economic sense than growing locally. “It’s far cheaper to buy [from] afar and ship to the distillery,” Keegan notes, and so “there’s no natural evolution of terroir.”

Proposing Subcategories

Krogstad points out that there has been something of a natural evolution to the American single malt category, and this might suggest a place to start a discussion of subcategories. Modern American single malt whiskey makers, he says, have generally emerged from three—or maybe four—points of origin.

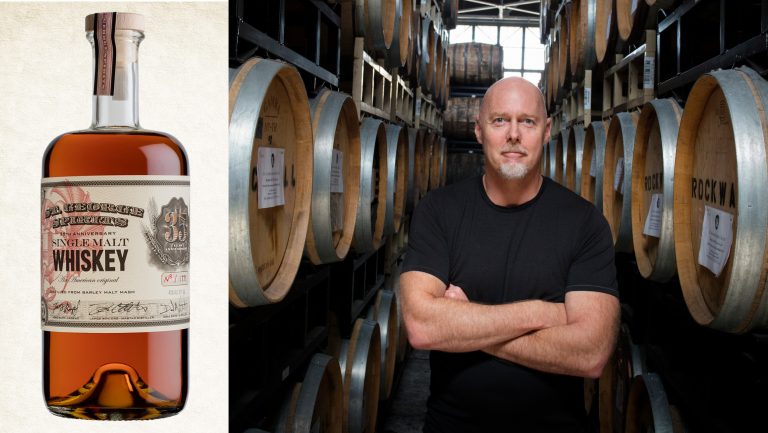

At the outset, a number of the recent whiskey makers arrived from the craft beer world—after all, malted whiskey is essentially distilled beer—and they therefore place a greater emphasis on the flavors that come from yeast and fermentation techniques. Krogstad, a former brewer, places himself in this category and notes that others who began their careers by making beer include Lance Winters, the master distiller at St. George Spirits in Alameda, California, and Randy Hudson, the cofounder of and distiller at Triple Eight Distillery in Nantucket, Massachusetts. “And Stranahans opened up next to Flying Dog Brewery,” says Krogstad, “and that was where they got their start.”

A second subgroup are those who emphasize the use of smoke to impart flavor, playing off the expectation of the peaty taste that defines many traditional Scotch whiskies. Corsair Distillery in Nashville produces a triple-smoke single malt using cherry, beechwood, and peat-smoked barley, and Andalusia Whiskey Co. in Blanco, Texas, uses traditional barbecue-smoking woods like oak, mesquite, and apple to smoke the barley for its Stryker single malt.

A third group, Krogstad says, are those whose focus is terroir, which reflects distillers’ drive to explore micro influences of terrain, grain, climate, and culture in carving out a flavor profile distinct to their distillery. Hillrock’s Baker and his colleagues approached their single malt with the land in mind. “We thought about it as terroir-based,” he says. “From day one we have been growing all our own barley, using organic principles, and have been harvesting and storing crops by individual field and then malting and distilling them by field. We feel that there are going to be some interesting differences among them.”

But Hillrock also employs some of the novel approaches of the other “subcategories” of American single malts “We’ve explored smoking with fruit and nut wood, and we’ve been trying the local peat,” Baker says. “But my view was that we didn’t want to make such an oddball product up front—one where people would say, ‘What the heck is this?’” As a bridge to its terroir-based whiskey, Hillrock has been distilling with peat-smoked barley malt imported from Scotland.

Westland Distillery in Seattle is also focused on terroir. ”Regionality is inevitable to a certain extent,” says Matt Hofmann, Westland’s master distiller, “and it will get more and more concentrated.” Westland uses barley grown in the Pacific Northwest, which is malted by a nearby maltster. Some of that malt has been smoked with locally-harvested peat, and those barrels of whiskey—the first of Westland’s to be made with local grain and peat—have now been aging for three years; Hofmann hopes that the result will be ready for the bottle in another two or three years. Westland has also released limited runs of Garryana, a whiskey aged in barrels made of Garry oak, a wood native to the region.

One aspect of terroir that’s often overlooked, Hofmann notes, is local culture. “I think something has been lost in the translation of terroir from French to English,” he says. “I think most people here think of terroir as strictly an environmental or agricultural proposition—the slope of the vineyard, the rocks, the soil characteristics—but when you speak to French people, they say that it includes the people.”

He adds that that’s especially true with whiskey. “Wine can ferment almost by accident,” says Hofmann. “But whiskey is a very deliberate thing.” Distillers use a tool—their still—to make their product, and that tool becomes part of the culture. “In the Northwest, we have a very progressive culture that’s not afraid to come up with a new idea and pursue it,” Hofmann says. “There’s a huge spirit of entrepreneurship. So that’s the way we look at raw ingredients.” It’s not about trying to replicate how whiskey is made in Scotland, but trying approaches that reflect the region.

Keegan follows a similar path. He speaks of “designing terroir”—that is, terroir is not seen as something that emerges organically, as happened in Scotland, but is created intentionally to capture local flavor. Toward that end, Santa Fe Spirits has released a mesquite-smoked single malt, whose flavor is linked to the area where the whiskey is made. “We chose mesquite smoke,” says Keegan, “because we wanted to be part of the region.”

Another possible distinction that can be made among malts is the wood used in aging—in particular, whether new barrels or used barrels are employed. “When people think American whiskey, they’re often thinking new wood,” says Moore, “looking for those sweet, vanilla-forward flavors.” Two different flavor profiles might start to coalesce around the selection of barrels, with outliers aged in different kinds of wood—like Westland’s Garryana—adding additional textures to the mix.

Looking Ahead

While ideas for categorizing American single malts vary—whether that means distinguishing whiskeys by regions or by motivations, by terroir or smoke or wood—one point producers seem to agree on is that history offers little guidance for the future. Ultimately, American single malt whiskey production lacks the history, regionality, and traditional techniques of Old World whiskey. And so what will emerge may well be wholly unexpected.

“I would love to see if a natural narrative emerges around urban versus rural,” says Hofmann. “It all boils down to whether the producers embrace the landscape around them.”

Keegan likes the idea of engineering terroir and creating a sense of place in a bottle, even if it’s done with ingredients that aren’t strictly local. ”It’s a place to start—and then let time and consumers sort it out on their own,” he says. “Discard what confuses or fails to clarify. Then double down on classifications that seem to work.”

American Single Malt’s New Horizons

A commission of distillers defines a new category that may put American single malt on the map—and on bottle labels

In Scotland, it took decades for regional styles to emerge, and there’s little reason to think that America—even with a surplus of can-do energy—will find a shortcut. Says Moore, “I think ultimately it’s far too early for us to figure out how we would stratify the different categories that we’re in.”

With time, however, that may change. “Sensible factions or categories may emerge,” says Triple Eight’s Hudson. “I’m hopeful, even though I’m jaded as hell.”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Wayne Curtis is the author of And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails and has written frequently about spirits for The Atlantic, Imbibe Magazine, Punch, The Daily Beast, and Garden & Gun, among others.