American single malt whiskey is ready to step into the limelight. That was among the takeaways from a 90-minute panel discussion with four American producers of single malt that I recently organized and moderated for Tales of the Cocktail 2017 in New Orleans.

Domestic single malt has been lingering in the shadows for more than a decade, but it’s now coming to prominence in the industry. As a result, distillers are assessing how to introduce the spirit and define its category more clearly, especially in terms of its similarities and differences with Scotch, Irish, and Japanese single malt—and how American variations tend to differ from one region of the country to another.

When whiskey drinkers order a Scotch, bourbon, or rye, they generally know what to expect from the spirit’s distillation process and flavor profile—within reasonably defined parameters. The Scotch Whisky Association and American federal regulators oversee and enforce guidelines for products in their purview, effectively laying down the lines within which the distillers may color.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

That’s not the case with American single malt whiskey, which isn’t currently recognized by the federal government as a spirits category. To address this, a group of about 60 American single malt producers—including all the panelists at Tales—came together in 2016 to form the American Single Malt Whiskey Commission (ASMWC) with the stated mission to “establish, promote, and protect the category of American Single Malt Whiskey.”

Defining a Category

The first step was to come up with a definition for the category, and the next, to persuade the federal government to incorporate the category into its “standards of identity,” under which liquor is classified. This development would allow producers to formally designate their products as American Single Malt Whiskey on the labels, which is currently permitted only by using confounding work-arounds.

A dozen distillers gathered in the summer of 2016 to start shaping what would soon become the ASMWC and to hammer out the definition for the category. “We thought it was going to be a knock-down, punch-’em-out fight, and we would all be bitter enemies for the rest of our lives,” says Matt Hofmann, head distiller at Westland Distillery in Seattle. “But within a half hour, we were all like, Okay, yeah, this makes sense.”

The Emerging Styles of American Single Malt

Distillers discuss three prominent subcategories that are making their way to the forefront

Some aspects of the definition proposed by the commission were borrowed directly from the Scottish whisky industry, which came up with its own definition for single malt several decades ago. For instance, one specification the definitions now share is that the spirit must be produced at a single distillery, which prohibits the creation of a blend from multiple producers. The ASMWC’s definition also calls for American single malt to be made from 100 percent malted barley, as is the case with Scotch, and to be defined geographically. It must therefore be made in the United States, just as Scotch must be made in Scotland.

But then come the differences. Broadly speaking, the Scottish single malt definition emphasizes tradition; the American definition leaves more room for experimentation and differentiation. “We don’t want to inhibit innovation,” Hofmann says. “We want to ensure that people can buy a single malt, get what they’re paying for, and get what they expect. But [we] also [want to] leave enough open so that people can innovate. That’s really the great strength of American single malt.”

Fewer Restrictions Than Scotch

Toward that end, American single malt production isn’t restricted to the use of a pot still, as it is in Scotland. Regardless of the still, the American definition calls for the whiskey to be distilled at 160 proof or less, ensuring that essential flavors aren’t stripped out. When it comes to barley, Hofmann says that the bulk of Scotch is made from barley processed in much the same way as for American single malt, with distillers being limited to 10 strains of barley (of 5,500 known to exist) that are approved by the Institute of Brewing and Distilling for their consistency of taste. However, the ASMWC has agreed to let producers work with a broader grain palate that includes roasted barley and barley smoked in nontraditional ways. Hofmann points out that some distillers in the Southwest use mesquite-smoked malt, whereas his company uses peat from the Pacific Northwest. “Both of those things are valid,” he says. “You have whiskey that mirrors what is grown around the country.”

Malting can also play a major role the flavor profile. “So many of the flavors are produced in that malting process,” says Christian Krogstad of House Distilling in Portland, Oregon, which has produced Westward Single Malt since 2005. He notes that malting is an essential part of beer making, and that three of the four Tales panelists moved into distilling from a brewing background—himself, Hofmann, and Rob Dietrich from Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey. For the past three decades, brewers have been eager to embrace innovations—including the expansive use of roasted malts to give deep flavors to stouts and other brews—and these three former brewers took that sense of innovation with them when they moved into distilling. Indeed, using roasted malts in making single malts is already one of the defining options that make American single malts unique.

The one malt producer on the panel without a brewing background was Gareth Moore of Virginia Distilling in Lovington, Virginia. Having launched in 2011, his distillery is among the newer producers on the single malt scene. Moore brought in experts in Scotch and Scottish-made stills with the intention of drawing on the best traditions of Scotland to make his single malt. But the idea wasn’t to replicate those traditions so much as it was to build and expand on them. One element that inevitably differentiates his single malt from Scotch is the heat of the Virginia hills, which can strongly influence aging speed and flavors.

A Bump in the Road

The process of creating a new, formal federal definition of American single malt began in earnest last year after federal regulators announced plans to update the more than 20,000 words of “27 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 5 – Labeling and Advertising of Distilled Spirits,” which had not changed significantly in a generation. The ASMWC met and discussed the new single malt category with the regulators last year and were making good progress, but the change in administration created a bump in the road. “Politics aside, whenever there is a [presidential] election, there’s a change in priorities in the Treasury Department,” says Hofmann, who has been an active member of the commission. “It’s fallen down the list of priorities, but we continue to push it forward.”

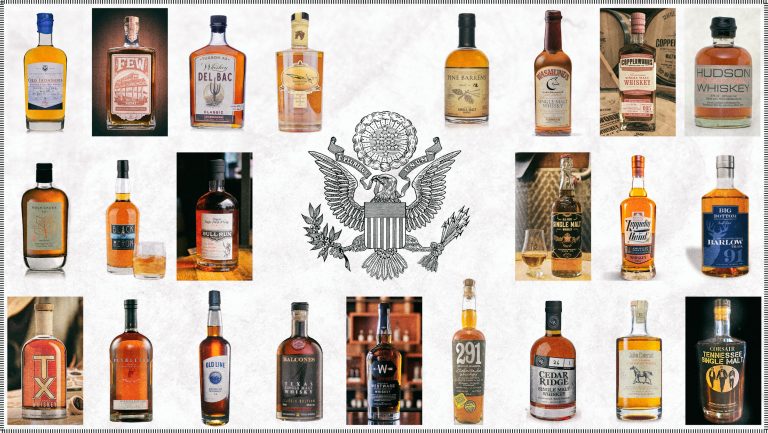

Although the time frame for the official creation of the American Single Malt Whiskey category is uncertain, the arrival of new products on liquor store shelves and back bars is not. An estimated 100 distillers in America are now producing malt whiskey from barley—and that number is certain to grow. Many producers are abiding by the definition even without federal oversight, anticipating that one day their product will join bourbon and rye as an official category.

It’s rare to witness the birth of a whole new spirit category, but that’s where we are with American single malt whiskey. You were here back when. Remember that.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Wayne Curtis is the author of And a Bottle of Rum: A History of the New World in Ten Cocktails and has written frequently about spirits for The Atlantic, Imbibe Magazine, Punch, The Daily Beast, and Garden & Gun, among others.