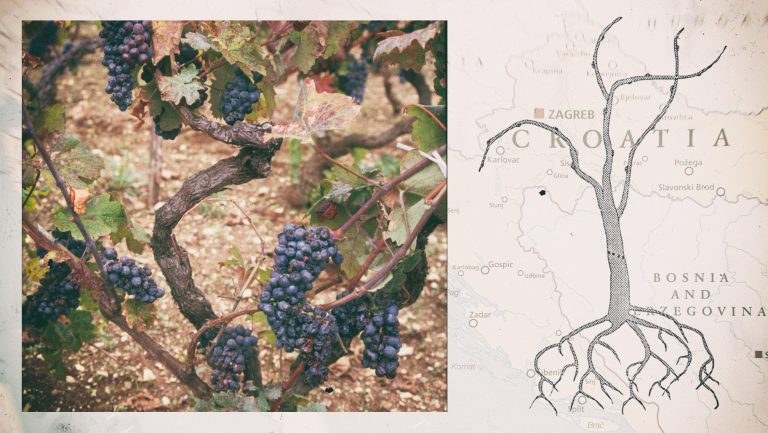

For decades, the origin of Zinfandel, the black-skinned grape that produces full-bodied, jammy red wines and several styles of rosé, was a mystery. Now painstaking work by wine researchers in Croatia and the United States have culminated in a landmark cuvée, to be released later this year, from grapes grown at Ridge Vineyards’ Lytton Springs property in Sonoma, California. For the past five years, Ridge has successfully grown an acre of Crljenak Kaštelanski, and an acre each of two other Pribidrag cuttings (“Pribidrag” is local variant name.). These three clones, discovered in Croatia’s Dalmatia region, were the key to pinpointing Zinfandel’s ancestral home.

“These [grapes] are what we lovingly call Croatian Zinfandel,” says David Gates Jr., gesturing toward rows of vines at Ridge’s hallowed Monte Bello estate in Santa Cruz, where the company has planted more Crljenak Kaštelanski and Pribidrag. Gates is Ridge’s senior vice president of vineyard operations, and he took a keen interest in the Zinquest saga, as he calls it. It’s an exciting time for Ridge: The Croatian Zinfandel cuvée from Lytton Springs, a blend all three clones, will mark the first time wine from these ancient grapes has been made in the U.S.

Vitis Archaeology

Finding these old vines wasn’t easy—it took years of work by scientists at the University of Zagreb in Croatia and by Carole Meredith, Ph.D., a professor emerita at the Department of Viticulture and Enology at the University of California at Davis. For Meredith, the search for Zinfandel’s origins began in the 1990s. The Zinfandel vine’s appearance made it clear to wine researchers that it was originally a European grape, but there were no records of the word Zinfandel being used in Europe.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

By comparing DNA profiles and historical records of different wine types, Meredith’s research team determined by the mid-1990s that Zinfandel had most likely originated in Croatia. In 1997, Meredith received an email from two professors at the University of Zagreb: Ivan Pejić, who specialized in the university’s Department of Plant Breeding, Genetics, and Biometrics, and his colleague Edi Maletić, who taught in the Department of Viticulture and Enology. Pejić and Maletić asked if she would be interested in working with them on a project funded by the Croatian government to investigate the country’s traditional grapes.

“There was concern,” says Meredith, “that [Croatia] might lose its viticultural heritage because economic globalization forces were pressuring Croatian growers to replace their traditional, and [to some] unpronounceable, varieties with international grapes like Merlot and Chardonnay. I told [them] I’d be happy to help because that would further my own interest in finding Zinfandel. Maybe one of those traditional Croatian varieties would turn out to be Zinfandel.”

And that’s exactly what happened. An ancestral grape, called Crljenak Kaštelanski, was found by chance in 2001 in the cliffside vineyards of Kaštela, a Dalmatian town just northwest of Split. It was plot-planted by grower Ivica Radunić’s father some 40 years earlier. The bud wood originated from a vineyard that his grandfather planted before that. The grape’s name, which means “black grape of Kaštela,” appeared to be a later-referenced localized identity.

After the chance Zinfandel find, a second safari headed out in 2002. This time the intention was to seek more clues about Zinfandel’s origin. The team stumbled on a grape that also looked like Zinfandel in a vineyard in Omiš, only there, it was called Pribidrag, a name remarkably close to Tribidrag, which is found in 15th-century literature. Says Gates, “They found evidence that Tribidrag was a favored court wine when Venice ruled the Mediterranean.”

There was also etymological evidence. The Italian name for Zinfandel—Primitivo—is derived from the Latin for “the first to ripen,” which is quite close to Tribidrag’s Greek translation as “early ripening.” Ultimately, Meredith, working with Foundation Plant Services (FPS) at U.C. Davis, found that Pribidrag was a DNA match for Zinfandel. The researchers decided to refer to the grape by its most ancient name: Tribidrag.

A Vine’s Journey

Once the ancient vines had been found, researchers—and winemakers—in the U.S. wanted to get their hands on them. “There’s a lot of perceived value in European grape plant material,” says Deborah Golino, the faculty director of FPS, alluding to vignerons’ desire for famous heirloom clones. In addition, the more genetic variation there is in a wine varietal, the better—genetic diversity helps plant populations stay resilient in the face of diseases or changes in climate.

“Most diversity from the species is at the area of origin,” Golino says. “Further away, you get a narrower genetic diversity. And if most [Zinfandel] from California came from plant material [that was] passed around, there hasn’t been time for genetic change.”

Once the Crljenak Kaštelanski and Pribidrag cuttings made it to the U.S., they—like all imported cuttings—went into quarantine at FPS. This step is necessary, because while some romance surrounds the idea of the suitcase smuggle—wherein cuttings are brought into the U.S. in luggage, without proper quarantining—it’s illegal to bring new plant material into the U.S. this way.

Suitcase smuggling is also ethically questionable. “If it’s your [European] village’s clone, it’s treated kind of like an intellectual property,” Golino says, which may add to the subversive mystique of smuggling in vines. But in Golino’s experience, “These [smuggled] vines don’t take well and usually end up being replanted.” In any event, FPS touches nearly every new and legally imported vine.

After researchers at FPS found multiple diseases on the Crljenak Kaštelanski and Pribidrag cuttings, the samples underwent shoot tip therapy, in which scientists peel away the exterior of the plant tip under sterile conditions. They then remove a minuscule shoot tip, which is only around 0.5 millimeter in diameter. This fragment of the vine has all of the genetic material in it but “for reasons not understood,” Golino says, “you get rid of viruses most of the time.”

FPS uses this pathogen-free material to regenerate clean plants. The process takes between six to eight months. From there, researchers establish the vines in the foundation’s vineyards. Ultimately, nurseries purchase plants from FPS and then sell them to growers. This is the path through which Gates acquired the Croatian Zinfandel cuttings at Ridge.

The Gain on Return: Tribidrag Goes Home

In 2013 the first virus-free Tribidrag selections were repatriated from FPS to Croatia, where winemakers can now plant clean, virus-free material. It’s this returned bud wood that has anchored many new plantings. “It was great to see the clean plant material reestablished in Croatia,” Meredith says. “I had never been a part of this kind of [exchange] before. And I don’t know of other examples.”

But it’s still a game of early-stage experimentation. The variety Plavac Mali was long thought to be Zinfandel, and although it turned out to be an cross of Tribidrag and another local variety, Dobričić, it’s still favored for winemaking in Croatia. “If you are a Croat and have been accustomed to these big, tannic, dry beasts, these [Tribidrag clone] Zinfandel vines don’t yield the same character,” says Eric Danch, a sales representative based in San Francisco for the Central Europe–focused importer Blue Danube Wine. That’s because of their thinner skin and consequently lighter red fruit character and overall brighter profile.

Still, Croatians are excited that the popular Zinfandel has been traced back to their country. It’s a point of national pride, and knowing Zinfandel’s origin helps with the marketing of Croatian wines. Croatia is also excited, says Golino, to compare its Zinfandel clones with those of California.

Having participated in the return of Zinfandel to its country of origin, Golino is eagerly awaiting new clones that may be discovered. The joint Croatian and American research has not only broadened FPS’s collection—it’s been a fruitful way to forge a symbiotic relationship among countries through the vine.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Peter Weltman is a sommelier and entrepreneur based in San Francisco who explores native grapes from ancient sources. He writes for global food publications, gives speeches on wine activism, and creates immersive experiences about his movement, Borderless Wine. Find out where he’s reporting from next on Instagram.