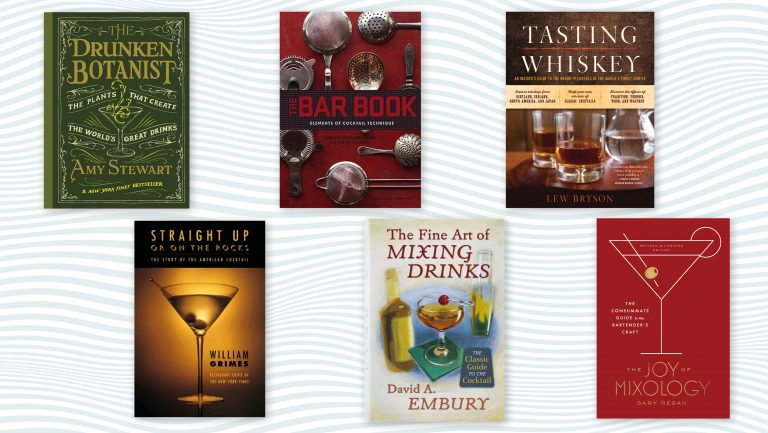

Books on spirits tend to belong to just a few camps. The cocktail book is certainly the most prevalent, though usually the least informative, save for a few classics. There are also the histories; they tend to focus on whiskey or rum. And finally, there are the single-subject books that center on individual spirit types—these are the primers on bourbon or mezcal or Scotch. That pretty much does it. But a small number of exciting, timeless books exist outside this simple order. They include Bernard DeVoto’s The Hour: A Cocktail Manifesto, first published in 1948, and Jeffrey Morgenthaler’s 2014 tome The Bar Book: Elements of Cocktail Technique.

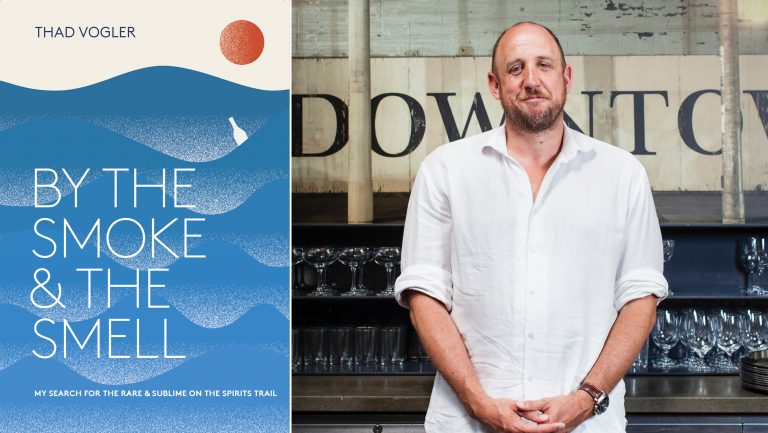

Thad Vogler’s new treatise, By the Smoke and the Smell: My Search for the Rare and Sublime on the Spirits Trail (Ten Speed), fits squarely into that latter group. It is at once a manifesto, a memoir, and a travelogue. It will likely hold a place as a classic in the collective imagination of spirits buffs and bartenders, brand managers and master mixologists, much the way sommeliers have found Kermit Lynch’s Adventures on the Wine Route a paean to the value of their work and philosophy. Vogler understands the context as well as the weight his words carry. He has read Lynch and is a much-respected barman. A graduate of Yale who paid his dues in many a restaurant, including San Francisco’s Slanted Door, Vogler went on to open Trou Normand and Bar Agricole, considered by many to be among the nation’s finest bars.

Vogler takes us with him on a quest for spirits that embrace transparency, authenticity, and integrity. We visit Calvados and Cognac, Kentucky and Cuba, and of course, Oaxaca. Along with his colleagues and friends, he seeks out “grower producers,” a term synonymous with quality in the wine world but probably unfamiliar to someone behind the bar. What Vogler calls meticulous sourcing, others have begun to call curation. Why? The idea is simple: A restaurant that prides itself on sourcing ingredients should extend that philosophy to bar. As Vogler points out, “I found it strange that there was something like Seagram’s 7 at a place that insisted on crediting farms on its menu…”

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Vogler’s reverence for craft spirits was born of experience. He writes, “It was at The Slanted Door that I decided that I wanted to connect guests to something beautiful, to a supply chain that wasn’t actively destroying the things we all claimed to be celebrating in this cultural moment: stuff like love, quality, relaxation, different cultures, and sexuality.” Familiar compatriots such as the importers Charles Neal and Ed Hamilton and producers like Judah Kuper of Mezcal Vago and Todd Leopold make appearances and reinforce the notion that Vogler is a man of firm convictions. Such staunch commitment can veer into the realm of isolation. Vogler admits that his Bar Agricole “arrogantly” boycotts the distributor of his friend Lance Winter’s St. George Spirits “because they handle a number of large brands.”

The book is filled with the name-dropping nonchalance of an insider whose talent, passion, and knowledge are sometimes undercut by his seeming unawareness of his own cool-kid status. There’s the constant tension of an us-versus-them mentality. While Vogler says that “this book is not a polemic argument; it’s a love letter,” it might feel as if it’s written only to those who already espouse the same values. For example, when he writes of visiting Camut estate, a truly noteworthy Calvados producer, the exclusionary tone may strike some readers as off-putting: “…we who have been there before know we are home, and the others, here for first time, are gripped by an appropriate deference, as Camut calvados is the shit.”

Despite his own admission that “we sell spirits for a living,” Vogler is skeptical of anything that reeks of branding or marketing. He laments that a favorite producer might change his packaging and therefore proclaims, “…a great producer really can survive if he is simply attentive to the quality of his product.” As someone who also sells spirits for a living, such a statement strikes me as willfully naive. I’ve seen many fine producers suffer for not recognizing the value in refreshing their label or bottle. The reality of selling spirits from small producers is harsher than one might think. Vogler admirably cops to this in one of the more poignant passages in the book, an account of an argument between his head barman Craig and the wine and spirits importer Charles Neal, in which Neal proclaims, “We can’t all be Bar Agricole!” We certainly can’t, but does that mean we shouldn’t try?

Vogler’s passion for honest spirits is reminiscent of the ethos for wine extolled in Terry Theise’s Reading Between the Wines. In this regard, Vogler succeeds in making his reader feel, rather than just understand, what’s at stake: Every cocktail contains the ingredients for a revolution—if we’re willing to hold spirits to the same high values we do for wine and beer.

The artificial barrier that has separated wine and beer from spirits has meant that during service, front-of-house staff would praise the virtues of the natural wine movement to guests only to retire for the evening with a shift drink of Modelo Negra (owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev) or an Aperol Spritz (Aperol is owned by the Italian conglomerate Gruppo Campari). To Vogler, this divide, naked in its hypocrisy, is unacceptable. What outrage would ensue if Alice Waters—one of Vogler’s inspirations—were to source her ingredients from Sysco? Or worse, enjoy an occasional Big Mac?

Early on, Vogler points out that the “real artists” are the producers, not the bartenders. In the wine world, sommeliers have long recognized that they are merely gatekeepers tasked with telling compelling stories to complement uncanny organoleptic experiences. With By the Smoke and the Smell, Vogler has bridged a critical gap. He convinces us of what we already know to be true but few have cared admit—that despite a beverage’s alcohol by volume, it’s the people behind the bottle and their values and humanity that matter.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Scott Rosenbaum is CEO of Ah So Insights, a wine and spirit industry newsletter and consultancy. Scott was formerly the vice president of T. Edward Wines & Spirits, a New York-based importer and distributor.