Of all the aroma compounds found in wine, terpenes seem to get the most attention and study. There’s something inherently alluring about the floral, rose, citrus, pine, and mint aromas most often associated with this group of compounds. Petrol and pepper are also a part of the greater family, adding to the olfactory diversity.

All grapes have terpenes—some bursting with them, others in quantities below sensory threshold, where they still may work synergistically with other compounds to affect aroma in indirect ways. There are more than 4,000 terpenes in the natural world, but only around 75 have been identified in grapes, and a few dozen in wine.

Most terpene-related wine conversations focus on what are known as monoterpenes (think floral, rose, and citrus) that are just one part of a diverse family of aroma compounds called isoprenoids. Although all grapes have monoterpenes, aside from a few varieties such as the Muscats and Gewürztraminer, they don’t define most wines. So, how can we more fully understand what we’re sniffing out? Here’s a quick breakdown.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Famous Florals

Let’s start with the famously floral Muscat, a classic example of a terpenic variety. It is a freak of nature when it comes to its monoterpene concentrations, such as in linalool, one of a handful of rose-scented terpenes, and one of the most common in grapes. In Muscat varieties, linalool can be found at nine times the level needed for sensory perception. In comparison, studies have found grapes such as Riesling and Albariño to have amounts hovering just around linalool’s sensory threshold level.

Even when aroma compounds are around or below sensory threshold levels, they may contribute to a wine’s aroma indirectly, notes Dr. Gavin Sacks, a professor at Cornell University’s Department of Food Science. Two such examples are Viogner and Albariño, which often have stone fruit character. “There is no one compound in them [that] smells like peaches, for example, but the near-threshold terpene levels have additive aromatic effects [that] with other compounds lead to their stone-fruit aromas,” says Dr. Sacks.

Geraniol is another rose-smelling terpene, and a hallmark of Gewürztraminer. At Stolo Vineyards in Cambria, California, winemaker Nicole Bertotti Pope makes cool-climate, dry-farmed, organic Gewürztraminer, just three miles from the Pacific Ocean. She usually notes a jump in terpene content when tasting grapes off the vine around 21 brix. “Some sunshine on the grapes is good for Gewürztraminer, it helps develop the aromatic compounds,” she says, noting that growing in cool climates seems to “keep the terpenic wines fresh, rather than tasting overripe or heavy.”

Bertotti Pope says that when pressing the grapes in the winery, the smell of rose petals is already pronounced: “Gewürztraminer is much more intensely aromatic at the juice stage than any other variety I’ve worked with.” This pre-fermentation intensity shows just how terpenic Gewürztraminer is, as a grape’s full monoterpene potential isn’t realized until fermentation (around 90 percent of monoterpenes in grape must are bound to other molecules and are non-aromatic until liberated during fermentation).

As aroma compounds, including monoterpenes, are the most concentrated in the grape skins, Bertotti Pope has increased the duration of skin contact over the years for her Gewürztraminer, starting with a few hours, and eventually increasing to 18 hours. “The longer the contact, the more I liked the result—the more of those compounds are extracted out into the wine,” she says.

The Wider—and Lesser-Known—Terpene Family

When most people describe a wine as “terpenic” they are usually thinking of a monoterpene-influenced variety. Yet terpene is a broad (and somewhat inaccurate) term, encompassing many categories of aromatic compounds found in nature. In fact, monoterpenes are not major—or even minor—contributors in most wines, explains Dr. Sacks. He suggests that when talking about wine, terpenes are more accurately classified as “isoprenoids,” which are then further classified by the amount of carbon atoms they possess.

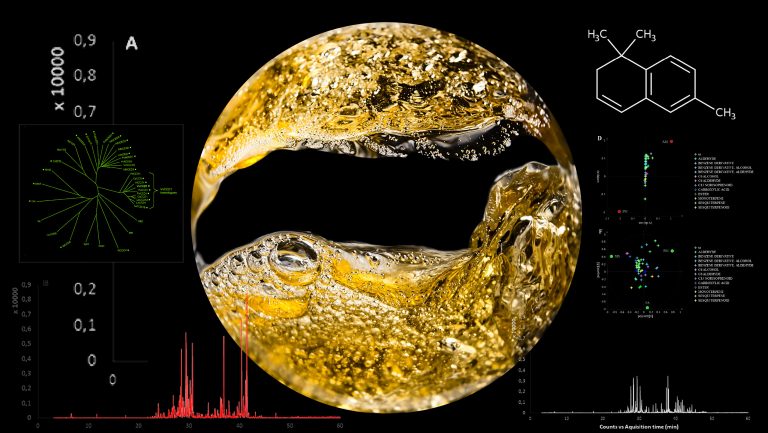

The norisoprenoid group, owing to their importance in a wide variety of grapes, may be the most essential of the isoprenoid family. They can express leafy, minty, fruity, floral, or even earthy notes, while others can increase or decrease the sensory threshold levels of other aromatic compounds. One of the best known is TDN (1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene) which contributes the petrol aroma to Riesling (aged Rieslings can have as much as 25 times the sensory threshold level of TDN). In comparison, Cabernet Franc can have TDN levels three times above threshold, and it can be found at around threshold levels in Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir. TDN concentration can increase significantly as a wine ages, thus the tremendous increase in petrol character that occurs in certain aged Rieslings.

Rotundone, which comes from the sesquiterpenoid group of isoprenoids, contributes the black-pepper aroma in Syrah and Gruner Veltliner. Dr. Sacks points to cool-climate versions of these grapes as examples with high levels of rotundone. “We don’t yet understand why cooler climates lead to higher levels of rotundone or other sesquiterpenes, it may be a response to disease pressure,” he speculates.

As wines age in bottle, the various isoprenoids develop in different ways. TDN, as noted above, may increase. Rotundone levels are highly stable over time. Many monoterpenes, such as Linalool and Geranol over a period of years, whereas others, such as Cis-rose-oxide (important in Gewürztraminer) is very stable.

Climate Change and Floral Taint

While climate change is usually associated with temperature increases, in certain areas it is causing colder temperatures. Winemakers in some northern latitudes are achieving ripeness late enough into the year that the grapes are still on the vine for the first freezes. In these areas winemakers have increasingly noticed a “floral taint” in some wines. Researchers such as Dr. Andrew G. Reynolds, professor of viticulture and plant physiology at Brock University in Ontario, Canada, have found the culprit. Rather than grapes, they found that the floral taint came from previously frozen leaves and petioles (leaf stalks) that made their way into the fermentations of mechanically harvested wines.

“Their presence, even at levels less than half a percent, greatly increased the various terpene and norisoprenoid levels, and was found to be causing the floral taint,” explains Dr. Reynolds.

Perhaps because of their showiness and accessibility, and the intense grapes for which they are known, monoterpenes often get the terpene spotlight, but it is important to consider the entire isoprenoid family for understanding wine aromatics. The family is large and diverse, and can affect wine aroma in many surprising ways.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Alex Russan, based in Los Angeles, is a former winemaker, importer, and sherry bottler. He writes about viticulture, enology, tasting and the nature of wine