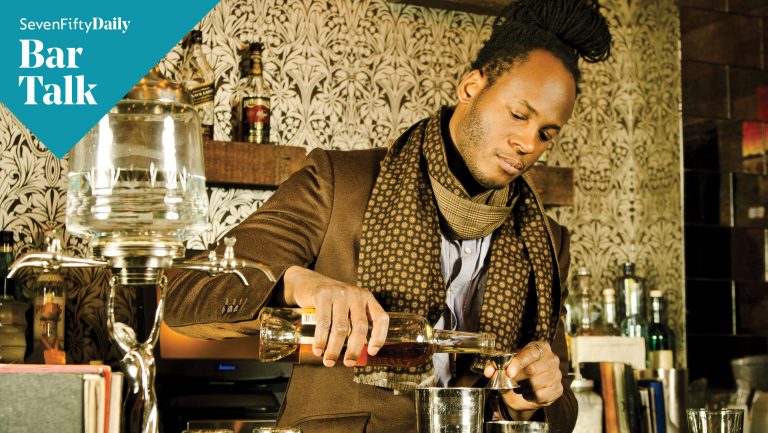

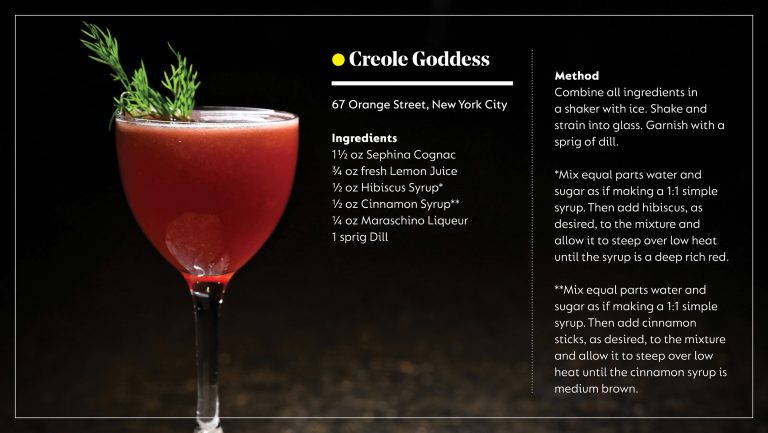

Karl Franz Williams is the owner of 67 Orange Street, the pioneering cocktail bar in New York’s Harlem neighborhood—where he first made a splash as the proprietor of Society Coffee—as well as the Anchor Spa in New Haven, Connecticut, minutes away from his alma mater, Yale University.

SevenFifty Daily: You have a corporate background. What led you to become an entrepreneur?

Karl Franz Williams: I opened Society Coffee in Harlem in 2005. I was a corporate guy being considered for a promotion at Pepsi and an entrepreneur at the same time. I had to decide: Do I want to do both or choose one? I was working in innovation on the next great Pepsi product and we hired Steve Olson [now of “aka wine geek” fame] as a consultant. That’s how I discovered the craft cocktail industry. It had history and I was just taken by it. I decided I wanted to leave Pepsi and open a bar.

What did you want to bring to Harlem when you opened 67 Orange Street in 2008?

It was the cocktail craft I was most attracted to. I wasn’t trying to open a nightclub. I wanted to create something unique, that stood out. It was extremely challenging at first. People just didn’t understand the concept.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

It was the first cocktail bar in Harlem, but never received the attention, say, of Sugar Monk, which arrived earlier this year. How does that make you feel?

The more people in the neighborhood making great drinks, the better. But I do get riled up when I hear Sugar Monk [credited as] the first or the only cocktail bar in Harlem. I have felt for a long time that we did not get our due recognition. Show me another bar that’s done what we’ve done, for as long as we’ve done it, and is still packed to this day, and you’re talking about Death & Co, PDT, and Employees Only, which have all won a ton of awards. What happened to us?

Why do you think you’ve been somewhat ignored?

People who look like me have not been a part of the conversation and there’s no good reason for it. The idea of what a great bar is, 67 Orange Street checks all these boxes: drinks, experience, fun, quality standards. I’ve been to cocktail bars all around the world, and I would put 67 Orange Street against any of them. There are some people who have tried to change the culture of the cocktail industry from the inside, like Colin Asare-Appiah [senior portfolio ambassador at Bacardi]. He has always been a voice, trying to pull people of color with him.

What specific actions can the industry take to become more inclusive?

There’s no quick fix. The systemic issues will take a while to break down. It’s about changing culture, which is hard to shift. It’s about making sure we are actively looking for opportunities to celebrate Black and brown businesses, even if they’re harder to find. That’s where access comes in. If you look back at all these early bars that had recognition and still get it, it’s all one family. Outsiders like myself had to peek through the curtains to try and learn what was actually happening. Access to capital is also a huge barrier to entry for qualified Black entrepreneurs. Ownership is ultimately the holy grail.

What are some of the challenges you’ve encountered?

It’s been a hard road, largely because I took risks in opening these businesses in a developing area. I was the first to bring artisanal coffee to Harlem and the first to bring craft cocktails. I was there before the neighborhood gentrified. I didn’t know the recession of 2008 was going to happen, but it happened. I needed money and I couldn’t get money; no one wanted to lend or invest. Call it a mistake, call it learning—you have to be very well funded so that you can ride the wave.

What are some of the reasons you think your bars have been successful?

I’ve always given our bartenders a platform and we create a community. There are 10 wooden stools with brass plaques affixed to them around the bar at 67 Orange Street. Regulars bought them and we call them “chairholders.” I also love being a guest at my own bar, overhearing conversations and experiencing what others are; it informs my decision making. I’ve tapped into historical stories for all of my projects. If something has a good legacy, I’m just trying to build on it.

More from Karl Franz Williams:

- His unconventional background: An electrical engineering degree, followed by corporate marketing jobs at Procter & Gamble and Pepsi.

- His love of history: 67 Orange Street is named for the address of Almack’s, one of the first Black-owned and operated dance halls to open in New York’s Five Points during the 1840s; the Anchor Spa traces its cocktail roots to the 1930s.

- On embracing diverse bar teams: “I’ve always had someone on my staff who was formerly incarcerated. These people have paid their debts to society and they are still blocked from having opportunities.”

- Every bar needs: “A tribe, its Norm from Cheers.”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Alia Akkam is a writer who covers food, drink, travel, and design. She is the author of Behind the Bar: 50 Cocktails from the World’s Most Iconic Hotels (Hardie Grant) and her work has appeared in Architecturaldigest.com, Dwell.com, Penta, Vogue.com, BBC, Playboy, and Taste, among others, and she is a former editor at Edible Queens, Hospitality Design, and Beverage Media. A native New Yorker, Alia now calls Budapest home. Follow Alia @behdria.