When designing a bar or restaurant, it’s far easier to get things wrong than right. In a space that may be thousands of square feet, even a few poorly designed inches can dramatically impact the flow of service or the comfort of a guest.

SevenFifty Daily spoke to a handful of designers and notable bar owners across the country to highlight some of the key hallmarks of a well-designed bar—and what design considerations have changed since the pandemic.

Getting the Music Right

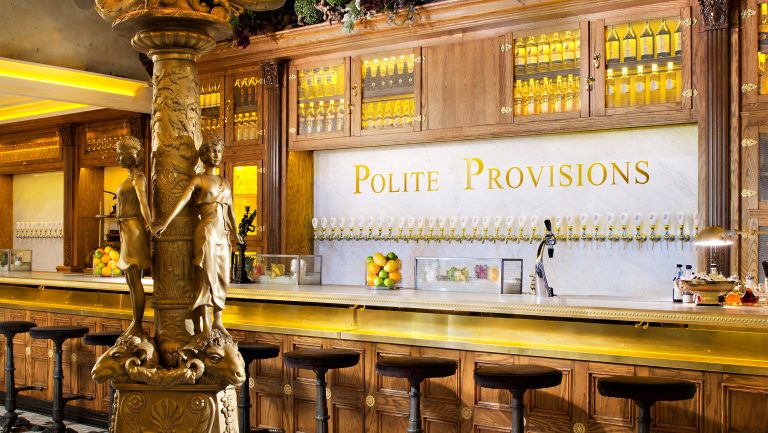

As soon as a guest steps in the door of a bar, design impacts that first impression. “What mood is the bar trying to create? That comes across right away with the lighting and music,” says Erick Castro, an owner of Polite Provisions and Raised By Wolves, San Diego bars known for their unique and ambitious designs.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

In an ideal hospitality environment, the best music strikes the balance between being omnipresent but not overpowering; in other words, loud enough to drown out adjoining areas, but not so loud as to hamper your own conversation. That sounds simple yet can take significant effort and cost to execute perfectly.

Sound dampening and absorption is often required to offset the many hard surfaces that are incumbent in a hospitality venue. Consistent decibel spread throughout the room is another consideration, to avoid overly quiet or ear-piercing areas. A great way to achieve this is by having a greater number of speakers throughout the venue. Greg Boehm, the owner of several New York City bars including Mace and Katana Kitten, says that his goal when designing a bar is to have no seat more than eight feet from a speaker.

Lighting Is Everything

Without a doubt, the most common design mistake is lighting. Whether by type, style, or location, lighting is as difficult to get right as it is critical to guest experience. The longer one talks with designers and operators about lighting, the more dictums, rules, and musts end up entering the conversation.

As a rule, lighting should be matched to the negative space of the ceiling. Functional lighting for the bartender is also critical, yet should not impact main bar space. Everything needs to be on a dimmer switch. And of course, there’s always the capacity for human error. “Even when the lighting is designed correctly, it can be ruined by staff leaving the dimmer switches too high,” laments Josh Harris, an owner of Trick Dog in San Francisco.

Additional switches and circuitry (meaning that more than one fixture isn’t tied to the same switch and dimmer) are worth every penny. The ideal Kelvin rating (a scale of color temperature in light bulbs) for most bar usage is 2200.

But this is a mere sample of the many intricacies of great lighting design. “Lighting is the great meeting of form and function. If you can accomplish both you’re either really good or lucky,” says Harris.

Creating Welcoming and Flexible Spaces

In addition to music and lighting, the physical design of a bar’s entrance is also critical in forming a positive impression. “If the first emotion the guest feels is confusion, then you’re creating a challenge for the quality of their visit, right off the bat,” says Stephani Robson, a lauded restaurant design consultant and professor for Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration. A properly designed entrance allows the guest to immediately ascertain whether there is a host or they should seat themselves, and whether there is table service or they should order at the bar, among other practical concerns.

It’s also important for the overall room or space to have flexibility. “How do you make a room that’s large feel intimate?” muses John Dye, formerly an architect and now the owner of several prominent and historic Milwaukee bars, including Bryant’s Cocktail Lounge and At Random.

Many bars make 40 percent or more of gross revenues on weekend nights, but a space that accommodates 125 revelers on a Friday also needs to feel comfortable on a Tuesday with just a handful of guests unwinding after work.

When referring to the layout of a room, owners often use the term “energy centers.” The main energy center of any bar is the physical bar itself, but a lounge or parlor seating area, large piece of artwork, or predetermined traffic pattern can also delineate an energy center. Astutely designed rooms will balance the energy centers and types of seating, avoiding a lopsided feel or having any dead areas (a spot that is usually the guest’s last choice).

What to Hide

A bar is a complicated apparatus that must accommodate a multitude of functions, many involving equipment that should, by necessity, be hidden from the guest. “How, why, and where the cleaning supplies are kept is key,” says Harris.

The point of sale (POS) machine is another example of something that must be accommodated in each design. “You want to make it as invisible as possible,” says John Bencich, an architect who founded Atlanta’s Square Feet Design with his wife Vivian and has designed Atlanta area hospitality spaces like Kimball House and Halfway Crooks.

The “often utilized but best neither seen nor heard” category also includes such concerns as refrigeration equipment, ice machines, air tanks for beer taps and soda guns, prep areas, dump sinks, trash, recycling, and perhaps even grease trap emptying. Ideally, these tasks are all accomplished while the guest retains the tacit illusion that everything within the bar happens with the same fastidiousness they see exhibited in their fancy drink and the shiny bartop it rests upon.

When Inches Save Dollars

Let’s say you’re ordering a Manhattan in a professionally designed, high-volume cocktail bar. The quick arrival of that drink typically connotes a plethora of infrastructural details, painstakingly designed and implemented, often at great cost.

The bartender reached for bourbon and vermouth, and likely did so within an 18-inch radius of their positioning. Functional lighting (even with the room properly dimmed) allowed them to see the many bottles in the well. After stirring, the mixing glass may have been cleaned on a star rinser to save a few seconds of using a sink. The used strainer was rinsed by a small foot-pedal-operated faucet, thus leaving the bartender’s other hand free to start on the next drink. “I watch how many movements it takes to make a drink or a round. If it takes a long time to make a three-ingredient drink it’s probably not going to be a profitable bar,” says Joaquin Simo, the proprietor of New York City’s Pouring Ribbons and Alchemy Consulting.

“People usually go to a bar to talk to someone, so the seating needs to make that easy… a pair of lounge chairs together should be at a 120° angle.” – Stephani Robson, restaurant design consultant and professor

Even the body angle of the bartender requires consideration. Simo notes that if the rail where drinks are built is even a few inches too far away from the bartender it can lead to lower back issues, elbow problems, or plantar fasciitis.

On the other side of the bar, there are a multitude of angles, measurements, and placements that all must align to create a comfortable visit for the guest. “People usually go to a bar to talk to someone, so the seating needs to make that easy,” says Robson. “For instance, a pair of lounge chairs together should be at a 120° angle.” The ideal height distance between a seat and table or counter surface is one foot. A bar foot rail should be six inches tall. Forty-two inches is the perfect bar height. Bar owners use these and other measurement standards (of which there are many) to attempt to create an ideal guest experience.

Design Considerations for New Bar Realities

Bars have been an integral part of society for several millennia, and that certainly won’t change. Bars have weathered plagues, wars, and everything in between. But with each cataclysmic societal shift, businesses grow and adapt. “You would be an irresponsible operator if you didn’t take [the pandemic] into account,” says Simo.

While none of the previously mentioned design fundamentals were altered by COVID-19, it added a host of other variables to consider. In considering real estate, many owners will be less favorable toward a location that doesn’t have the possibility of outdoor seating. “Businesses, cities, and local governments have realized that people love to drink outside—it would be foolish for regulations not to move forward [with that],” says Castro.

While in the past a host stand may have only needed to house a few menus and a notebook or iPad, now there may be numerous additional requirements: sanitizer, an infrared thermometer, masks, and other safety items. Guests are also more aware of safety and cleanliness now, which entails more attentiveness from the staff.

Designers and bars are already integrating pandemic-related safety concerns into their operations. In time it will be just another of the myriad details that go into opening a bar and creating the right experience for a customer.

In the end, what exactly makes the difference between a great and memorable experience and a lackluster one? It comes down to a combination of hundreds of factors, angles, measurements, and design decisions, many of which are decided long before the guest ever steps into the bar.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Chall Gray is the author of The Cocktail Bar: Notes for an Owner & Operator (White Mule Press, 2018), co-owner of the acclaimed bar Little Jumbo in Asheville, NC, and a principal of the bar consulting firm Slings & Arrows. He lives in Asheville, NC with his wife and son.