Classically, to infuse flavor into a spirit, the crucial ingredient is time. Combine botanicals and liquor in a container, seal it, label it, and wait days or weeks while the soluble flavor compounds leach out of the plant and into the liquor.

A bar can turn necessity into a virtue, with prominently displayed jugs of pineapple slowly steeping in tequila, or horseradish in vodka, but time and space are costly. And long infusions are indiscriminate in what they extract; care and experience are therefore needed to avoid flavors that are unpleasantly overextracted or unbalanced.

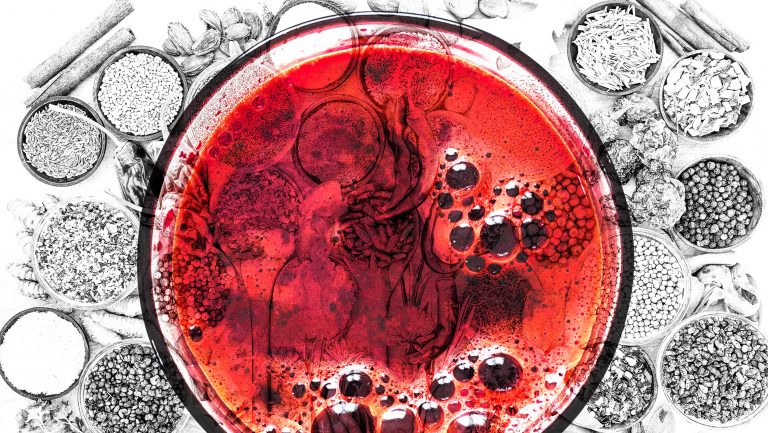

Though they aren’t necessarily drawbacks, these aspects of classic infusion have spurred bartenders to develop new, faster techniques—versatile ways that allow them to capture a desired flavor in minutes. There are a few approaches to rapid infusion, but the essential principle is the same: the liquid and solid ingredients are forced into more intimate contact through modification of pressure, temperature, or both.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Positive Pressure

In his book Liquid Intelligence, which has played a significant role in popularizing such innovative techniques, Dave Arnold writes, “Rapid infusion is neither better nor worse than traditional long-term infusion, just different.” Arnold’s preferred method uses pressurized nitrous oxide gas in a whipped-cream siphon (a cream whipper costs about $100 and a box of 24 charger cartridges is approximately $20). Pressure forces the gas into the liquid and the liquid into the solid; dropping the pressure back to normal causes the liquid to bubble back out of the solid. Both steps of the procedure disrupt the pores of the solid material, and moving the liquid back and forth facilitates the extraction of flavors.

The basic procedure is as follows: In a clean iSi cream whipper, combine a spirit and a flavorful solid ingredient, cut into pieces to expose a lot of surface area, and seal the whipper snugly. Then insert a nitrous oxide cartridge, charge the whipper, and shake it. Then charge with a second cartridge, raising the pressure even higher. After a few minutes, with the whipper upright and holding a cup over the nozzle to catch any wayward spray, squeeze the lever to vent the pressure rapidly. Then unscrew the top, wait for the bubbling to die down, and strain the solids out of your infused spirit.

The speed of the infusion lends itself to experimenting, trying new flavor combinations and seeing what works. Fruits and herbs are common infusables, but anything is fair game. “You can cycle through 10 iterations of a recipe in one day,” Arnold says in his book. “For their first try, tell people to do fresh turmeric,” he tells SevenFifty Daily. “That color is amazing.”

Eamon Rockey, who teaches a class on rapid infusion at the Institute of Culinary Education in New York City, where he serves as the director of beverage studies, says, “It’s a great way to capture beautiful fresh flavors. In a basil infusion, you want it to be the freshest basil experience possible, and the pressure process is the way to get that.”

Alex Felland, the operations manager at Fresco, a restaurant and lounge in Madison, Wisconsin, agrees that fresh ingredients—specifically, those containing water—are the best for rapid infusions. “Dried [or] hardened ingredients, not as much,” he says, although he does have a recipe for a piña colada variant that features vodka rapid-infused with toasted shredded coconut.

As a general rule, rapid infusion extracts more bright flavors and fewer spicy and bitter flavors than slow infusion. “[It] will typically shift flavor toward the high notes,” says Arnold, “and shift away from the base notes. You can get more of the floral stuff and less of the vegetal stuff.” But to get the desired amount of flavor in the final product, he stresses, you need to use more of the source ingredient than you would in a traditional infusion. In addition to the ingredient cost, says Rockey, “I always try to remind people that when you’re doing a rapid infusion, you’re not just paying for the vodka, you’re also paying for the gas. Each of those canisters costs money.”

The hardest part of nitrous infusion, says Arnold, is managing the variables to ensure consistent results from batch to batch. “The mistake everybody makes is to forget that the amount of liquid and the size of the container directly relates to the amount of pressure you get, and the amount of pressure directly relates to how the infusion is going to taste.”

In select cases—when you don’t mind the infusion becoming carbonated—you can do a large, economical rapid infusion in a keg connected to a tank of carbon dioxide. “The greatest thing about that is it’s running on constant pressure, a little bit below 100 pounds per square inch. It just makes life a lot easier when you don’t have to calculate the volume of liquid and the number of chargers.” Nitrous oxide comes in large tanks too, but they’re tightly regulated as both a drug and a combustible, so a bar would need both a dental license and special precautions to obtain one.

AJ Sedjat, a bartender at Area 31 in Miami, favors rapid infusions primarily for their speed, which allows him to make custom cocktails on the fly. “Area 31’s terrace is busy, and the rapid infusions help us create great cocktails quickly, without compromising flavor.” Even “aged and smokey meats can be added to bourbon,” he says, “to create an on-the-fly whiskey [drink].”

The Science of Ice in Cocktails

Bartenders weigh in on shape, size, cut, and clarity—and how to choose the right ice

Negative Pressure

Given the choice, Rockey prefers using a chamber vacuum sealer instead of a cream whipper to achieve rapid infusions. “It creates an outer-space-like environment that boils everything out, then forces it back in, which is a very effective way of transferring flavor from one place to another,” he says. “And once you buy the vacuum machine, you’ve made the investment, and you can use it as many times as you want without paying a buck or two each time.” The machine typically costs between $2,500 and $3,000.

In this method, the solid ingredient and the liquid ingredient are placed in a vacuum bag together and put into the machine, which draws an initial vacuum. Under these conditions, the air inside the solid expands and exits, damaging cells on its way—”like a sponge that you’re wringing out,” says Rockey. When the vacuum is released, the liquid surges into the vacated pores.

At this point, you can stop and serve the solid, which is now translucent and saturated with flavorful liquid—Arnold fills apple slices with curry oil using this technique—or you can repeat the vacuum-and-release cycle, forcing the liquid in and out of the solid at least twice to transfer flavor from the solid to the liquid.

Note, though, that in a number of states (including New York), the use of a vacuum sealer in a bar necessitates not only the space to house the hefty machine but the “reduced oxygen packaging” required by the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point plan, a food safety management system that applies to any business that uses a vacuum sealer.

Temperature

A different approach to rapid—or semi-rapid—infusion uses the controlled heat of a sous vide bath to speed the process. The general technique is to set an immersion circulator in a water bath for no higher than 77.5°C (171.5°F), combine the ingredients in a Ziploc bag, evacuate the air, seal the bag, and submerge it. The higher the temperature, the faster the infusion, but “77.5 is a very important number,” Rockey says, “because it’s about a degree below the boiling point of alcohol. Cross that point and suddenly you have a bomb” as the ethanol in the mixture turns to vapor and expands, bursting the bag. An immersion circulator costs approximately $200.

These infusions generally take closer to an hour, although Rockey has a recipe for an à la minute vodka infusion with classic gin botanicals. “We were taking black pepper and juniper, fresh and dried citrus peels, and cardamom, coriander, fennel, and bay leaf, doing a 90-second infusion in a single portion of vodka to produce a ginlike spirit that we could then chill very quickly and serve right away.”

Heat does more than just speed things along. It also causes transformations in the ingredients themselves, softening plant cells and accelerating enzyme activity that changes flavors. Fresh ingredients will start to take on “cooked” flavors, which can be good or bad. Herbs are notoriously sensitive to heat: The enzymes that naturally cause browning (chiefly polyphenol oxidase) become highly active at higher temperatures. So even a brief hot steep will produce the off-flavors variously described as “brown,” “grassy,” “swampy,” and so forth.

So for fresh, delicate ingredients, a cool infusion is better. Sous vide infusing, however, “works great with dried ingredients in particular,” Rockey says. “That elevated temperature really helps to open up the botanicals.” Conversely, dry ingredients like spices and dried citrus peels “won’t be great” in a cool rapid infusion, he says. “There’s not enough time for it to hydrate, so the flavors’ solubility is very limited.”

At Existing Conditions, the house-made orange bitters are created with a combination technique—pressurized with nitrous oxide and heated. “When I want to extract a lot of flavor, including bitter notes,” says Arnold, “I’ll heat the infusions up.”

What if you have an ingredient that’s dry or bitter but you don’t want to risk the flavor changes associated with heating? Time may still be the best ally. “Honestly,” says Rockey, “that’s when you have to say, ‘Rapid is great, but I’m not going to try to cheat this. I’m going to allow this ingredient to sit in a solution for a few days, a few weeks—for a time sufficient that I get the flavor I want.'”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Paul Adams is the senior science research editor at Cook’s Illustrated. He lives in New York City, where he writes about food and drinks.