Researchers from The Australian Wine Research Institute (AWRI) describe rotundone, the chemical compound responsible for the peppery flavor in some grapes, such as cool-climate Syrah or Shiraz, this way: If you were to add just one drop to an Olympic-sized swimming pool, the water would taste of pepper.

The AWRI began trying to identify the origin of Shiraz’s peppery notes in 1999. An extensive study of the 2002 and 2003 vintages sampled grapes from 18 vineyards across southern Australia, including the cool, mountainous Grampians region, where the oldest block of Shiraz at Mount Langi Ghiran winery mysteriously and consistently expresses profound peppery notes. Damien Sheehan, the chief viticulturist and general manager of Mount Langi Ghiran, describes the grapes from this block as “a real explosion in the mouth.”

Now, much more is known about rotundone, yet there are a few lingering mysteries. In global wine regions where rotundone is present in grapes—in Duras from South West France’s Gaillac region, in Graciano from Rioja, and in Vespolina and Schioppettino from northern Italy, for example—researchers have examined the impact of temperature, light, time, water, soil composition, clone selection, maturation, and foliage to try to grasp what spurs rotundone production in grapevines, and in turn, whether it’s possible to achieve consistency in peppery notes in wine across vintages.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Rotundone: Tiny, Powerful, and Enigmatic

In 1967, rotundone was first identified by researchers in Poona, India, in the bulb of a weedy nutgrass known as Cyperus rotundus (hence the name rotundone), which lacks a peppery aroma. It’s since been detected in rosemary, thyme, marjoram, basil, chicory, grapefruit, oranges, apples, mango, and wine grapes, according to a 2020 study compiled by researchers Olivier Geffroy, Didier Kleiber, and Alban Jacques at The University of Toulouse’s Purpan Engineering School.

“The swimming pool image is easier to visualize than a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer,” says Tracey Siebert, Ph.D, a senior research scientist with the AWRI. The chromatograph pulls compounds out one by one during chemical analysis while a spectrometer tracks the amount of each. A researcher provides additional verification via an olfactory smell test.

Rotundone eluded detection for years as it’s present in grapes in mere nanograms, appearing in chemical analyses as a tiny bump rather than a peak; it’s also possible to have anosmia, or loss of smell, for rotundone, making it that much harder to detect.

In 2007, AWRI shared its major finding that rotundone was the source of peppery notes in Australian Shiraz, a result gleaned from extensive testing of the sample sets from 2002 and 2003. Alpha-guaiene, a sesquiterpene compound, is the base of rotundone, and isn’t aromatic on its own—but when alpha-guaiene is coupled with oxygen, rotundone is created. “The proper chemical name for it is as wide as a page, so we stick with rotundone,” says Dr. Siebert.

Sesquiterpenes are a substance of only carbon and hydrogen and can assume a variety of shapes. Siebert likens rotundone to other unmistakable aromatic compounds like 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (better known as TCA or cork taint) and vegetal pyrazine compounds in Sauvignon Blanc. For each, the shape of the molecule meets the shape of our olfactory receptors in a potent way.

Rotundone has since been identified in a diversity of grapes, including varieties from New Zealand, France, and the U.S. Given the many global microclimates where rotundone is expressive, it remains a mystery what exactly spurs rotundone production, or what exactly the plant might be defending itself from that in turn accelerates rotundone production.

Plants make sesquiterpenes to defend themselves against herbivores, pests, predators, and fungi, or to signal insects they are ready for fertilization. Given rotundone’s intrinsic defensive properties, it could be relevant to how pests like the spotted lanternfly can be repelled through natural means, a focus at Pennsylvania State University’s College of Agricultural Sciences.

Alongside that, “It would be nice to understand how the variable weather conditions associated with climate change will impact rotundone production, especially early in the season, before the shift into rotundone production,” says Michela Centinari, Ph.D, an associate professor of viticulture at Penn State.

Dr. Centinari and fellow colleagues reached out to the AWRI in 2016 for assistance creating a detailed chemical analysis of Noiret, a hybrid grape planted widely in northeastern U.S. “We were first thinking, could it be that the peppery notes in Noiret are due to rotundone, even though there is no obvious, direct connection from a parent genealogy point of view with Shiraz?” Noiret is a hybrid of Steuben and NY65.0467.08. Pennsylvania’s growing season is also comparatively cool and short compared to many Australian regions, and there are differences in soil composition, sunlight, pests, and herbivores. Yet, analyses indicated that some Noiret grapes exhibit more peppery notes than some Shiraz.

“The next question was, can we modulate the amount of rotundone in the grapes to affect the concentration?” says Centinari. As it’s unknown exactly what external stressor rotundone defends grapes from, it’s not readily viable to modulate or control rotundone production—but a cooler climate presents one throughline that can be leveraged.

Factors Impacting Rotundone Production

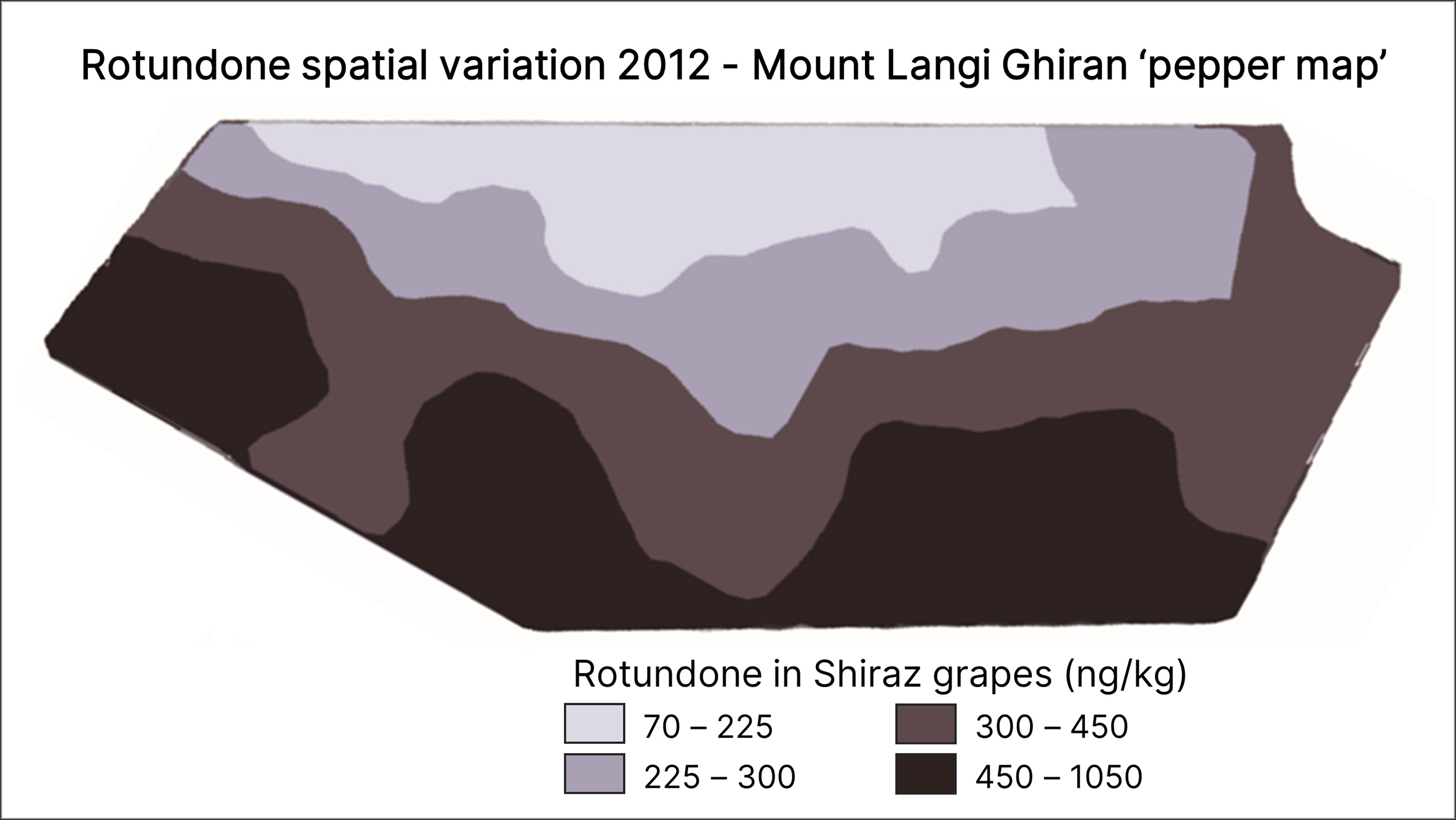

AWRI and CSIRO researchers sampled 177 Mount Langi Ghiran vines during three growing seasons—2012, 2013, and 2015—alongside others from Australia, New Zealand, France, and later, the U.S. They aimed to understand why some parts of a vineyard capture rotundone’s peppery flavor and aroma profoundly, while other vineyard blocks show no peppery character at all. This study resulted in a “pepper map,” or a heat map, showing what Sheridan Barter, a senior scientist with the AWRI, calls a “beautiful gradient” that describes consistent differences in the sections of the vineyard where rotundone accumulates across all three seasons, even when there are seasonal variations in the mean amount of rotundone accumulated. The study found that vineyard variations in soil and topography are the most driving factor in terms of differences in rotundone accumulation.

Barter also describes wide variations in rotundone accumulation between vintages, such that winemakers cannot anticipate the same concentration from year to year. For example, in 2013, rotundone reached 1,000 nanograms per kilo in AWRI’s study, and in 2015, just 37 nanograms per kilo. It is again unknown precisely what accelerates rotundone production, but further study of the relationships between particular growing environments and grapes’ subsequent chemical composition might inform how strategies like late harvesting (as rotundone appears toward the end of a cool growing season) can be leveraged to increase the concentration of rotundone in cool-climate Shiraz.

“We have a long, cool, drawn-out season, and get complex flavors where pepper stands out,” says Adam Louder, the winemaker for Mount Langi Ghiran. Louder compares these notes with warm-climate Shiraz from the Barossa Valley or McLaren Vale, where, he says, “flavors of rich fruit, cloves, and baking spices are more prominent.”

A few years after the initial study, Centinari and colleagues similarly noted that rotundone concentrations were much lower at warmer Pennsylvania growing sites. “We found cool regions produce 10 times more rotundone than sites in southeast Pennsylvania, where it’s much warmer,” says Centinari. “We don’t know why, but it’s a strong effect.”

Researchers have also explored how sunlight and warmth affect rotundone production. Centinari shares an example of a Pennsylvania grower who experimented with pulling leaves from around the fruiting zone, increasing sun exposure and finding a slight increase in rotundone production. AWRI researchers have also put alpha-guaiene on filter paper in differential light. “With no light, it takes a long time to form rotundone from the base compound,” says Siebert. “In sunlight and laboratory light, it forms quickly then degrades quickly. With a shade cloth in place, it forms not as quickly and stays around for quite a while.”

Siebert concludes, “Too much light probably breaks it down. So, it’s likely made and then broken down by the bright light in the hotter, brighter part of summer. Or it might not be made until the plant needs to protect itself from something we don’t know—and that part we can’t ask the plant, unfortunately.”

Can Rotundone Be Coaxed in the Winemaking Process?

Centinari distinguishes between the task of identifying rotundone and quantifying it, to possibly affect its concentration in wine. While some viticultural practices, like leaf removal, selective harvesting, and in some instances, irrigation practices, have led to a slightly higher concentration of rotundone, or hint at the possibility of affecting a wine’s peppery character, vinification techniques like different maceration times, yeasts, enzymes, as well as cold soaking grapes, thermovinification (flash détente), and carbonic maceration have shown little correlation to increased rotundone.

Rotundone is primarily present in the grape skins, and extracts readily once alcohol production begins. “If you take the skins off quickly, you can get less rotundone,” says Siebert. “But there’s not much way of getting more out.”

A research team at the Sensory Evaluation Center at Penn State concluded that heightened rotundone in Noiret could be off-putting, or, as Centinari says, “More is not always better—it’s better to a certain point.” Previous studies of Duras and Syrah in the northern Rhône, conducted by Geffroy and fellow researchers, found similarly there can be a threshold between desirability and too much, particularly in Duras. All sensory studies of rotundone have confirmed that some consumers will not detect it at all, or have anosmia for this compound.

However, many people find rotundone’s peppery notes to be an attribute in Australian Shiraz. “We love it when we get it, but we don’t hold out for it,” says Louder. In years when rotundone is present, Louder watches the temperature carefully during fermentation to “keep the integrity of the fruit profile and the spice profile.” In Louder’s experience, a cooler fermentation temperature can help hold onto the desirable spice flavor that rotundone provides in Shiraz.

When rotundone is powerfully concentrated, “It smells fantastic in the winery—that’s the best smell you can get,” says Sheehan.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Amy Beth Wright is a creative nonfiction writer and journalist covering wine, food, and travel. She contributes to Wine Enthusiast, Fodors, and The Alcohol Professor, among other outlets. Keep in touch on Instagram @amyb1021 and Twitter @AmyBethWright. Visit amybethwrites.com to read more of her work.