This advertising content was produced in collaboration with our partner, Wines of Roussillon

Tucked into a southern corner of France, nearly crossing over the Spanish border, Roussillon is an overlooked wine region that’s now making its way into the spotlight. France’s last remaining viticultural frontier, this wild region has its own distinct identity—and wine professionals are finally noticing.

“Roussillon has old vines and a savoir-faire that comes from making wines for thousands of years,” says Caleb Ganzer, the managing partner of Compagnie des Vins Surnaturels in New York. “Now, that’s being combined with relatively cheap land and people who have embraced the organic and biodynamic movements. It’s the right time for the right place, along with people doing the right things to garner attention.”

Roussillon’s dramatic landscape harbors decades-old vines and remarkably diverse soils, and this wealth of natural resources—along with the land’s affordability, a byproduct of its under-the-radar status—is luring new winemakers to the region. Together with some of the region’s pioneers, these producers are crafting a wide range of characterful, dry wines that over-deliver at their price points.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

A Distinctive Identity

Nearly all wine textbooks (and many restaurant lists) lump Roussillon in with its eastern and much larger neighbor, Languedoc, labeling the two “Languedoc-Roussillon” and making broad generalizations about climate, geography, and wine style. However, the two are very different.

“Roussillon is both geologically and culturally separated from the Languedoc,” says Ganzer. While Languedoc maintains a firmly French identity, Roussillon’s ties reach toward its neighbors across the Pyrénées.

“This is really French Catalonia, and the Catalans are fiercely independent,” adds Victoria James, the beverage director and partner of Cote in New York. “Grouping it together with the Languedoc does it a disservice.” For evidence of Roussillon’s Catalan roots, just look to its dishes; fried fish is just as much a staple on local tables as hearty meat dishes like boles de picolat, a Catalan dish of meatballs and olives in a spicy sauce.

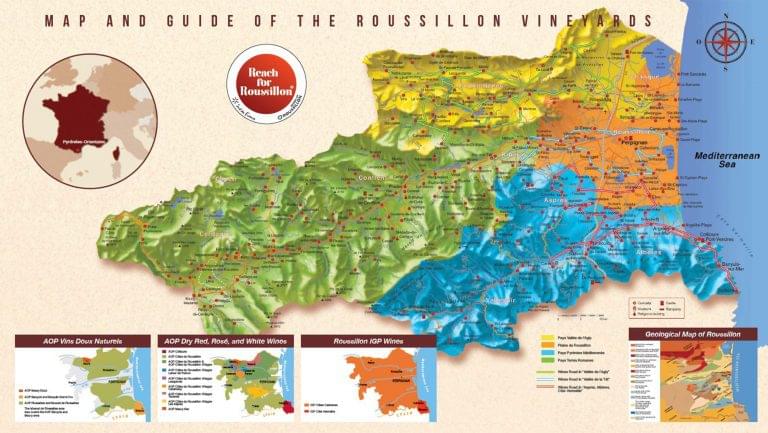

Compared to the wide swath of land that the Languedoc occupies, Roussillon is a small pocket of viticulture—but it packs an incredible amount of dimension and diversity into its land. A sunny, dry amphitheater open to the Mediterranean Sea and surrounded on three sides by mountains (the Corbières to the north, the Pyrénées to the west, and the Albères to the south), Roussillon’s terrain is rugged, with rocky vineyards planted on slopes as the land makes its way from mountain to sea.

“You have the Pyrenees Mountains that fall into the Mediterannean Sea, and it’s an interesting conflux of these two features,” says James. “As a result, you get a lot of freshness and structure but also sun-soaked energy from the Mediterranean, and those briny, iodine notes.”

The region’s complex patchwork of soils and subsoils adds to the wild topography of Roussillon. “It’s one of the most geologically diverse regions in France, located on a fault line that has exposed geological activity from millions of years ago,” says Ganzer, who is so inspired by the region that he (along with Compagnie chef Eric Bolyard) plans to open a new restaurant in New York inspired by regions on both sides of the Pyrénées in 2021. Soils, which are often so hard that it’s impossible to dig out a cellar, include clay, limestone, schist, granite, and gravel across the region’s 14 AOPs and two IGPs.

Eight types of wind sweep across Roussillon, the most significant being the Tramontane and the Marinade—keeps disease and pest pressure low. Not only does this make Roussillon an ideal area in which to work organically or biodynamically, but it offers the right conditions for vines to dig deep and thrive for decades. Gnarled, old, low-yielding vines are a fixture of the region’s vineyards.

The Dramatic Shift from Sweet to Dry

Though Roussillon has garnered fresh attention in recent years, its viticultural history dates back to the 7th century B.C., when the Greeks first planted vines here. However, much of the region’s wine history was defined by sweet wines, specifically the fortified vins doux naturels. A regional specialty, Roussillon is credited with having invented the process of mutage, or fortification, thanks to Arnaud de Villeneuve in the 13th century.

As consumer tastes shifted toward dry wine, Roussillon was largely forgotten. Its mountainous boundaries were difficult to traverse, and investment and attention were redirected to more hospitable climes. But some early adapters saw opportunities to pivot, using the region’s natural resources to make high-quality wines.

“They’ve learned to adapt a wine region that was developed to make vins doux naturels to modern times,” says Ganzer, pointing to efforts to use Muscat grapes—traditionally used to make vins doux naturels like Muscat de Rivesaltes—for dry, skin-contact orange wines.

Today, over 75 percent of Roussillon wines are dry, largely made from the same grape blends used for the region’s traditional vins doux naturels. All three Grenache grapes—Noir, Blanc, and Gris—are used to create a wide range of wines, as are red varieties like Carignan, Lledoner Pelut, Mourvèdre, and Syrah, and white varieties like Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains, Muscat of Alexandria, and Macabeu.

Even regulations have adapted—the vins doux naturels AOP Maury, for instance, was updated to allow dry wines to be labeled as Maury Sec. This shift toward dry wines has also allowed U.S. trade members to better introduce these wines to consumers. “Dry wines are a much easier sell than sweet wines right now,” says Brent Kroll, the proprietor of wine bar Maxwell Park in Washington, D.C., “so it’s much easier to turn people onto their dry wines.”

Next-Gen Winemakers Arrive

Among the 2,334 family-owned vineyards, 417 private cellars, and 28 cooperatives shaping Roussillon’s wines today are both multigenerational legacies and transplanted newcomers. Producers like Domaine de la Rectorie and Domaine Cazes have been part of the region’s transformation and transition to dry wines and organic practices for over a century.

Ganzer credits pioneers like Gérard Gauby, who began estate-bottling when he took over his family’s Domaine Gauby in the 1980s, with kickstarting a new era of winemaking focused on organic viticulture and minimal intervention to produce characterful, dry wines. “He’s super generous with his time and education, and he’s willing to foster a new generation of winemakers,” adds Ganzer.

By the turn of the 21st century, a new generation had started to emerge, attracted by the prospect of working with old vines in intriguing soils using organic, biodynamic, and natural techniques. It also helped that the relatively low price of land in Roussillon was attainable even for independent, experimental producers. Locals had new opportunities to purchase wineries and land, launching estates like Mas de Lavail and Clos Saint Sébastien, and there was an influx of newcomers from outside of Roussillon as well.

“You [had] a lot of younger folks moving down or moving back to the Roussillon,” says Ganzer. This includes French winemakers like Cyril Fhal of Clos du Rouge Gorge (from the Loire Valley) and Marjorie and Stéphane Gallet of Roc des Anges (from Côte-Rôtie and Normandy, respectively), as well as international transplants like Tom Lubbe of Domaine Matassa (a New Zealander who grew up in South Africa) and Dave Phinney of D66 (the American creator of Orin Swift).

Outside proprietors and investors took notice as well, like leading Rhône producer Michel Chapoutier, who purchased Bila-Haut; Parisian executive Olivier Decelle, who purchased Mas Amiel; Languedoc pioneer Gérard Bertrand, who makes a full range of wines partnering with the cooperative of Tautavel; and Paul Mas Estate, which bought Domaine Lauriga.

Offering a Full Stylistic Spectrum—Plus Value

Though much of the new attention for Roussillon wines is credited to dry wines, this fervor has also brought renewed interest in the region’s traditions. “When a region gets shaken up, that’s interesting, and then you find out why that region was there in the first place,” says Jeff Harding, the wine director at the Waverly Inn in New York.

Professionals note that there’s much to discover within the region’s vins doux naturels as well, which comprise 17 percent of the region’s current production. Made from both white grapes and red, in both aged and unaged styles, vins doux naturels have a wide stylistic range.

“There’s a huge playground within the profiles of these sweet wines, from the primary fruit and floral notes of Muscat to the aged, savory notes of both red and white vins doux naturels,” says Ganzer. “It’s really a treasure trove, and there are so many overlooked styles.”

Vins doux naturels also offer great options for back-vintage lovers. “It’s so hard to find aged sweet wines like port, Madeira, and Sauternes that are readily available in the marketplace,” says James. “A lot of these vins doux naturels offer that, and they aren’t as pricey because they aren’t as well known.”

Due to the many terroirs, grapes, producer philosophies, and wine styles, it isn’t easy to classify a singular style of Roussillon wine. “I don’t know if you can stylistically categorize these wines because there are so many expressions,” says James. “They are wines with a unique sense of origin and they represent an independent culture.”

However, that’s part what makes Roussillon such a universally appealing region. There’s something for lovers of crisp whites and bold reds, richly sweet wines and refreshingly dry ones, obscure offers and friendly crowd-pleasers. “In a restaurant, you’re not always dealing with people who want geeky wines,” says Ganzer. “You’re dealing with people who want full-bodied reds and dry whites, and Roussillon wines can be both, which is what I love.”

Because of their under-the-radar status and the lower costs of land in the region, Roussillon wines also tend to overdeliver for their price points. “The wines are very compelling and reasonably priced for the quality,” says Ganzer. “At every price point, you’re really getting value and paying for what’s in the glass rather than [a price mark-up from] the name.”

Now that winemakers, wine professionals, and consumers are newly discovering Roussillon, it won’t remain an untouched viticultural frontier for long. But with its strong Catalan identity, unique terroirs, and long history of winemaking, the energy and interest in this special wine region will only serve to increase the quality and availability of these delicious wines.

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.