This advertising content was produced in collaboration with our partner, Wines of Germany.

Few wine-producing nations on earth breed the kind of obsessive, almost cult-like levels of devotion that Germany engenders in the hearts of its die-hard fans, and it’s not difficult to understand why. Laying claim to one of the world’s oldest, richest, and most complex wine cultures, the country offers an unparalleled case study in diversity.

Historically, Germany’s claim to fame has always rested upon the extraordinary quality of its Rieslings. For centuries, Riesling from the country’s top vineyards has endured as a benchmark for white wine greatness, celebrated for its elegance, transparency, and unmatched knack for transmitting the subtle nuances of terroir. Capable of assuming a kaleidoscopic spectrum of styles, from bone-dry to decadently sweet and every register in between, over the past two decades the category has captured the imagination of beverage professionals across the United States.

In restaurants and wine bars, German Rieslings of all styles have become indispensable sommelier “secret weapons,” given their uncanny ability to pair with a wide range of cuisines and culinary influences. More recently, however, as members of the trade develop a deeper appreciation for Germany, becoming better acquainted with its fascinating grab bag of grapes and the distinct identities of its 13 wine regions, the country’s versatility is on greater display than ever before.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Geography

As public taste skews toward wines that display greater freshness and elegance, countless wine-producing areas pay lip service to crafting “cool-climate” wine styles. In Germany, however, that is more than just a buzzword. Encompassing some of Europe’s northernmost vineyard areas, Germany provides the textbook example of true cool-climate winemaking.

To successfully ripen grapes in some of the world’s coolest vineyards, some of which sit as high as the 51st parallel, every opportunity for ripeness matters: the slope of the vineyard, exposure to sunlight, and proximity to rivers (including the famous Mosel and Rhine), to name a few. The result is a vibrancy, distinctive acidity, and mineral tension that comes across not only in Germany’s classic white wines, but its reds and sparkling expressions as well.

History

Wine has been a fact of life in Germany ever since the Romans introduced viticulture to the Germanic territories. That happened over 2,000 years ago, beginning on the banks of the Mosel River sometime between 50-150 BC and extending to the Rhine in the centuries that followed. By the 8th century, the Frankish Emperor Charlamagne’s efforts to advance the cause of Christianity played a pivotal role in both spreading and regulating viticulture and viniculture.

Throughout the Middle Ages, monasteries were central to the development of Germany’s wine culture; in fact, several top wineries still in existence today were originally founded as monasteries. The first recorded mention of the Riesling grape (spelled “Riesslingen”)—from a cellar log in Hessische Bergstrasse—dates to March 13, 1435, a day that each year is now celebrated as the official birthday of Riesling.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that German Riesling achieved international renown. During this “golden age” of German wine, the top vintages from the Mosel and Rheingau regions regularly graced the tables of royalty and fetched higher prices than even Bordeaux or Champagne on top restaurant and hotel wine lists.

From the late 1800s through the middle of the 20th century, however, the phylloxera epidemic and two World Wars temporarily dampened the momentum of German wine. That trend continued with the rise of mass-market Liebfraumilch during the first decades of the post-war era, leading many U.S. consumers to (mistakenly) view all German wine as sweet.

Over the past 50 years, with the better delineation of growing regions and vineyard sites, the introduction of a new system of wine laws in 1971, and a surge of highly ambitious world-class producers, Germany has entered its next golden age. Today, awareness of German wine in export markets has reached unprecedented levels, and wine quality has never been higher.

Key Regions

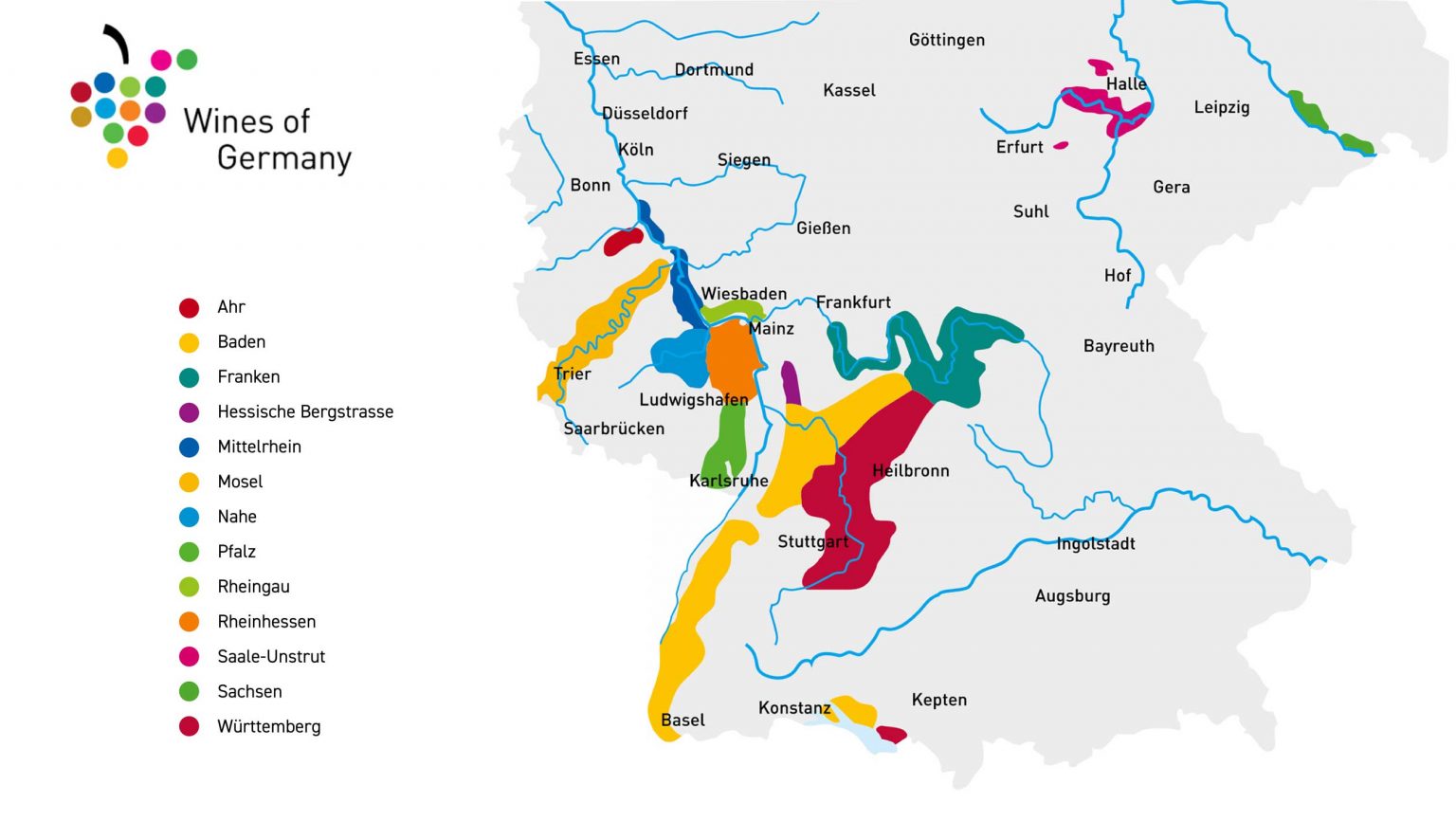

Set in the south and southwest parts of the country, each of Germany’s 13 regions is home to unique climatic, geographic, and geological conditions, and terroir plays a significant role in Germany’s wines. This is precisely what makes Germany such a fascinating study in contrasts.

Mosel

As Germany’s coolest wine region, the Mosel’s marginal climate imparts a completely unique profile to its wines. The extremely steep, terraced slopes that grow along the banks of the region’s eponymous river (and its two tributaries, the Saar and Ruwer) give birth to Germany’s most delicate, light-bodied, and ethereal whites, notable for their chiseled acidity, purity of fruit, and low alcohol. The high percentage of slate found in the Mosel’s soils also impart a finely etched mineral character that has become the region’s calling card. Though it has long specialized in mesmerizingly fruity, off-dry styles, today the Mosel also turns out equally compelling dry expressions.

Rheingau

As the Rhine turns west just past the Lower Main, the world-renowned Rheingau region, home to many of Germany’s most iconic estates, sits on the river’s northern bank. It was here, in the town of Johannisberg, that the country pioneered the rich, late-harvest, spätlese style of riesling for which Germany became famous in the late 18th century. Though it still produces the stunning off-dry and sweet wines that earned it international renown in centuries past, today the Rheingau has channeled that innate capacity for ripeness into some of Germany’s most powerful and age-worthy expressions of Riesling, as well as a recent renaissance of top-notch Spätburgunder, or Pinot Noir.

Rheinhessen

Extending across the rolling hills on the opposite southern side of the Rhine from the Rheingau region and encompassing some 26,500 hectares of vines, Rheinhessen is not just the largest wine region in Germany, but also one of the most diverse. The area’s rich mosaic of soil types allows for the cultivation of a wide range of grape varieties, both red and white. Once associated with sweet, mass-produced Liebfraumilch, Rheinhessen has more recently attracted a new generation of innovative and open-minded winemakers, making it one of Germany’s most exciting regions to watch.

Pfalz

Located south of the famed vineyards of the Mosel and Rheingau, just across the border with Alsace, the Pfalz is Germany’s second largest region and specializes in richer, more voluptuous styles of wine, boasting apricot and peach flavors rather than pear and green apple. While Riesling still takes center stage here, the area’s Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris have attracted attention lately, along with a growing raft of deeply-colored reds, including Pinot Noir, Dornfelder, and Portugeiser.

Baden

If Germany is primarily known for its fragrant whites, the southernmost region of Baden turns that time-honored paradigm upside-down. The warmest and sunniest of all of Germany’s production zones with over 1,700 annual hours of sunshine, the area has recently been turning heads within the progressive sommelier set as a hotbed for cutting-edge reds. Among them, Pinot Noir has revealed special promise, combining juicy red fruit with racy acidity and subtle earth. A smattering of top-notch Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc can be found as well.

Key Grape Varieties

Though Germany is best-known for white wines, particularly Riesling, local vintners produce a diverse range of wines from different grape varieties throughout the country’s regions. About 34 percent of Germany’s vineyards are devoted to red wine varieties, which thrive in warmer regions like Baden and Pfalz.

In addition to still wines, Germany has a long history of producing sekt, or sparkling wine. The category has recently undergone a quality revolution, driven by a raft of artisanal producers who craft cool-climate bubbly that capitalizes upon Germany’s natural assets: lively acidity, minerality, and freshness. The best derive their fizz from the traditional method of secondary fermentation in bottle.

Riesling

Germany’s hallmark, Riesling is grown in every German wine region. Though it always maintains its signature acidity, it is incredibly terroir-sensitive, which contributes to the huge range of Rieslings produced here, from bone dry to lusciously sweet, feather-light to robust.

Pinot Noir

The third-most planted variety in the country, Germany is the third largest producer of Pinot Noir in the world, only after France and the U.S. Pinot Noir has proven to produce some of Germany’s finest red wines, dominating plantings in the Ahr and Baden, where it can produce quite an array of styles. Germany’s Spätburgunders range from delicate and refreshing to robust and complex, at times on par with the quality (and price) of sought-after Burgundies.

Pinot Blanc

Called Weissburgunder locally, Pinot Blanc crafts delicately fruity, fresh wines, typically with a slightly nutty aroma. The grape is on an upswing in Germany, where plantings have doubled over the past decade, and Germany is now the largest producer of Pinot Blanc in the world.

Pinot Gris

The pink-hued Pinot Gris, called Grauburgunder in Germany, can produce exceptionally complex, long-lived white wines with notes of tropical fruit, nuts, and spice, particularly when it is aged in oak. Here again, plantings of this grape have grown significantly since the turn of the millenium, and Germany is the third largest producer of the grape worldwide.

Silvaner

The cultivation of Silvaner in Germany dates back more than 350 years, and it was once the country’s most important grape variety. With subtle aromas and juicy flavors, it is a traditional variety of Rheinhessen and Franken, where it is bottled in the region’s signature Bocksbeutel.

Lemberger

Known as Blaufränkisch elsewhere in Central Europe, Lemberger is becoming increasingly popular, particularly in the southern region of Württemberg. With typical notes of blackberry, cherry, and fresh herbs, they may be light and fruity or concentrated and tannic.

German Wine Styles

It is a common misconception among wine professionals that German wine is unnecessarily confusing. It is indeed complex, as this country encompasses a dazzling range of styles, from bone dry (or trocken) to sweet, white, red, rosé, and sparkling.

But German wine doesn’t have to be complicated; if anything, Germans are notoriously precise. Once you grasp the basics of the terminology, you quickly realize that a German wine label conveys an enormous amount of information, telling you exactly what to expect when you open the bottle.

German wine law classifies the country’s wines into four main quality categories, from the broadest geographical designation to the most specific.

Deutscher Wein is the most basic classification, and grapes can be sourced from vineyards anywhere in Germany. Landwein may be made from one of the country’s 26 Landwein regions, similar to the French Vin de Pays. Qualitätswein (QbA), which literally translates to “quality wine, is regulated by strict production standards and must come from one of Germany’s 13 official winegrowing regions.

Prädikatswein represents the apex of Germany’s quality hierarchy, where wines must fulfill the requirements of a specific Prädikat, or ripeness level. The six Prädikats outlined below refer not to the amount of sweetness in the finished wine, but to the sugar levels (and therefore potential alcohol) in the grapes at harvest.

- Kabinett: The least ripe Prädikat, and therefore typically the lightest wine in a producer’s profile, Kabinett wines are often bottled with just a touch of residual sugar, which finds a perfect balance with their palate-cleansing acidity. It’s safe to expect the faintest kiss of sweetness unless the word “trocken” is printed on the label indicating a dry wine.

- Spätlese: Literally translating to “late harvest,” Spätlese refers to fuller-bodied wines made from optimally ripened grapes. Though traditionally made in the classic, fruity style, it is increasingly common for producers to ferment to complete dryness, yielding a richer, more concentrated expression.

- Auslese: Meaning “select harvest,” Auslese wine grapes are harvested even later than those destined for Spätlese, after high levels of sugar have accumulated. They are most often—though not always—rendered in a dessert wine style.

- Beerenauslese: Only made in the most fortuitous vintages, when the grapes ripen to uncommonly high levels of sugar and are often covered by the noble rot Botrytis cinerea, this is where German wine enters full-blown dessert wine territory. Virtually indestructible in the cellar, the best Beerenauslese wines can age for several decades.

- Trockenbeerenauslese: Boasting the highest concentration of sugars in the entire Prädikat system, these decadent rarities are some of Germany’s most lusciously sweet expressions, produced from grapes that have shriveled into raisins on the vine; they are often enveloped in botrytis as well.

- Eiswein: As its name would suggest, Eiswein is German for “ice wine,” produced from grapes that have literally frozen on the vine, intensifying their sugars and yielding a completely unique style of sweet wine defined by unusual depth and complexity.

Though it falls outside the Prädikat system, Grosses Gewächs (GG) is another important style designation to note. A special classification used by the Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter (VDP), an association of Germany’s top wine-producing estates, Grosses Gewächs designates a dry wine that comes from a top-ranked vineyard known as an Erste Lage, the group’s equivalent of grand cru. Embodying a new paradigm of seriousness for dry German wine, GG has taken the wine world by storm, showcasing a whole new side of Germany.

What’s Happening Today in German Wine

For a wine culture that spans centuries of heritage and tradition, Germany’s modern wine industry has paradoxically emerged as a hotbed of innovation, thanks in no small part to a recent influx of forward-thinking producers who have started experimenting with new ways to grow and make wine.

Though climate change presents winegrowers with new challenges, it has also resulted in a renaissance of red winemaking in Germany. Never before has the U.S. market enjoyed a wider spectrum of German reds—a trend that shows no signs of relenting with the growing vogue for lighter, refreshing styles.

A leader of organic and biodynamic farming, Germany now boasts the third-highest number of Demeter-certified biodynamic wine estates in the world. Across the country’s 13 winegrowing regions, natural winemakers have started to carve out an alternative narrative about the country’s wines, breathing fresh energy into its traditional styles while experimenting with avant-garde techniques like pétillant naturel and skin-fermented whites.

Even as Germany embraces a new wave of fuller-bodied, powerfully dry versions of Riesling, epitomized by the rise of the premium Grosses Gewächs category, a growing number of producers have also embraced an ambiguous style known as feinherb. Though it lacks a legal definition, the term refers to “dry-ish” or “dry-tasting” wines that occupy a fascinatingly delicious middle ground between off-dry and fully trocken. Often the result of spontaneous yeast fermentations, where sugar levels are left to be determined naturally, the style has become a calling of the country’s new minimal-interventionist avant-garde.