“Ginger, garlic, red chiles, at some point sumac, harissa, coriander, za’atar.” As I pulled apart the buttery kubaneh bread he set before me, Jonathan Aubrey recited the spice profile of chef Meir Adoni’s pan–Middle Eastern cooking at the three-month-old Nur in Manhattan’s Gramercy neighborhood. It’s these flavors that Nur’s 30-year-old general manager, a former Eleven Madison Park maître d’, is tasked with matching on the wine list.

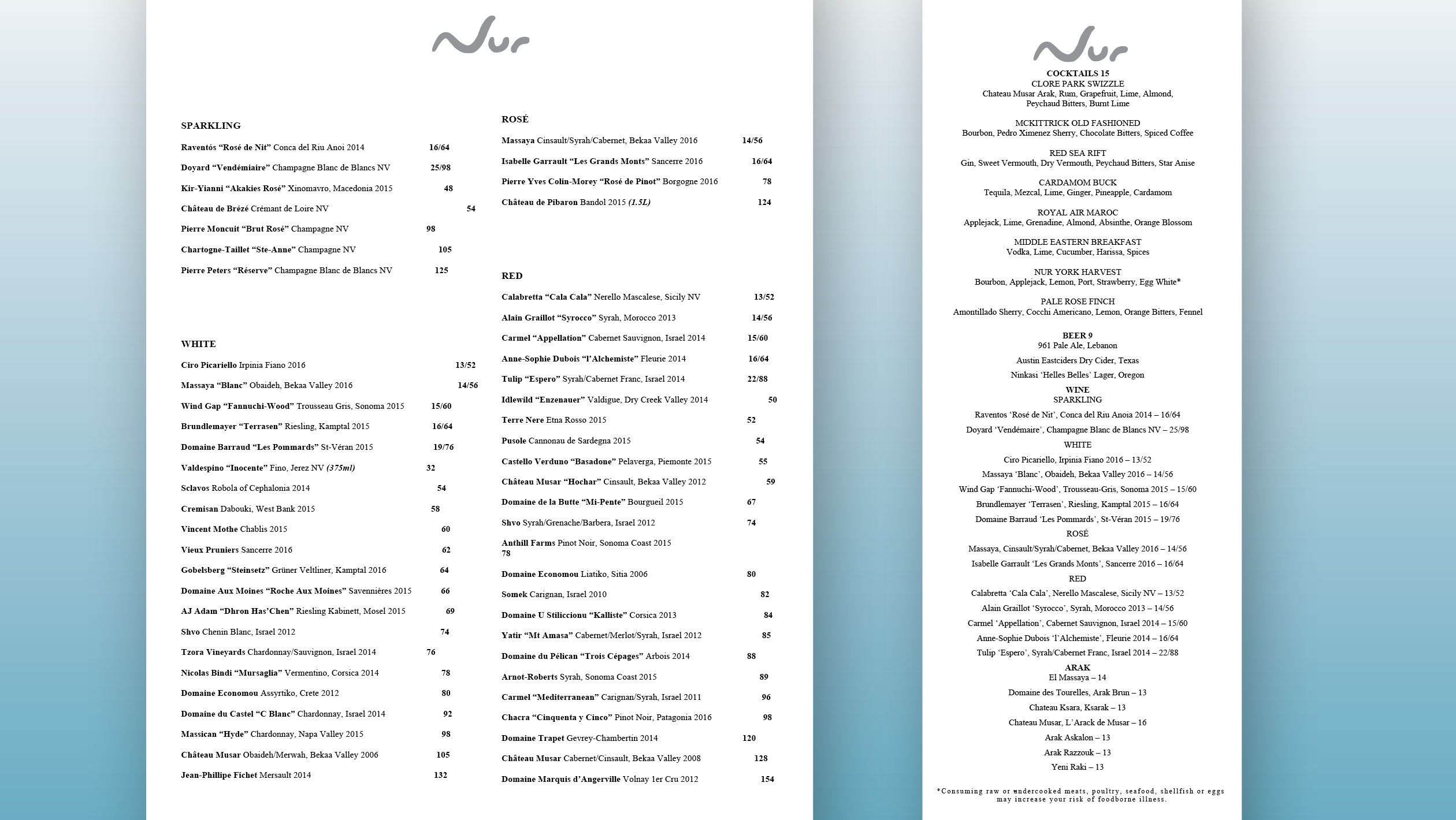

Aubrey’s complementary goal is to introduce diners to the wines of the Middle East. With the help of an Israeli consultant, Gal Zohar, Jeff Kellogg of Kellogg Selections, and former Nur wine director Ted Damianos, Aubrey put together a list on which Lebanon, Israel, Turkey, and Morocco represent a third of the 56 bottles. Where a California Cab would clash like plaid with polka dots, these wines complement Adoni’s food. It’s a win-win strategy for the menu and the list.

Take the Yemeni-style brioche I was eating. It was dotted with peppery nigella seeds and served with the Yemeni hot sauce called zhug. The Chenin Blanc Aubrey poured with it wasn’t one of the usual suspects but a wine from Shvo Vineyards in the Upper Galilee. Its savory nose mirrored the spice; its warm-climate tropical notes meshed with the warm brioche. Sitting on Nur’s list along with a more-familiar Savennières from Domaine Aux Moines, it showed Chenin Blanc in a new light.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Listed for $74, it seemed steep at first compared with the Savennières’ $66, but in fact Aubrey takes a bottle-by-bottle approach to his margins, pricing the Middle Eastern wines more approachably, so guests can try something new. Israeli wines come at a premium, which limits Aubrey’s choices. “We want to expose people to these,” he says. “That’s why it’s so important to find that balance [in price point] and not push them too high.”

No Middle Eastern restaurant’s list would be complete, for instance, without wine from Lebanon’s cult producer Chateau Musar. At Nur, guests can spend $128 for a 2008 vintage of the producer’s top-end Cabernet-Cinsault blend, or get their feet wet with a 2012 Cinsault for $59. The program is all about creating options. “That’s why you see a traditional Chablis there,” Aubrey says. “But if you want to try something different, go for the Massaya Blanc.”

Nur’s list describes this wine as “Obaideh, Bekka Valley 2016,” noting its appellation and its Chardonnay-like indigenous grape. Such compact descriptions provide quick lessons to Nur’s clientele. “We try to educate,” says Aubrey. “The Middle East is the heart of winemaking. If you go back centuries, that’s where it started. It’s important for us to pay homage.”

The son of a Moroccan Jewish mother, Aubrey grew up in a kosher household; his family split its time between Paris and New York. He spent summers in the south of France, where his grandfather rolled couscous by hand. His life experience is as steeped in the Middle East’s polyglot flavors as his wine list is. But his dedication to the region isn’t dogmatic.

“If you like Riesling or Grüner, I’m not going to bring anything from Israel. I’m going to let the Austrians do what they do best,” says Aubrey, who threw some of these varietals on the list because they go so well with spicy food. “I’m not going to jeopardize quality and pick something from the region just because it’s from the region.”

Of the remaining two-thirds of Nur’s wines, several come from the southern Mediterranean: Corsica, Sicily, Greece. But the list also includes Arnot-Roberts Syrah from the Sonoma Coast, Bandol’s Chateau de Pibaron rosé, Pierre Péters “Reserve” blanc de blancs, and a premier cru Volnay from Domaine Marquis D’Angerville—coveted bottles for wine drinkers who know what they want.

It sounds complicated, and for Aubrey, who sources all these wines, it is. Israeli Wine Direct, Skurnik, Grand Cru Selections, Polaner, Winebow—he works with six or seven distributors, a juggling act for such a small house. But Nur’s one-page list, organized simply by increasing price under sparkling, rosé, white, and red headers, is easy to navigate. And by placing an Israeli Chardonnay next to one from Napa Valley, the list drives home the point that less familiar places produce wines on par with the tried and true.

Nur’s glassware supports that philosophy. Every wine is poured into a Riedel Degustazione red wine glass. The universal glass makes service easier in this busy restaurant. But it also erases the hierarchy between, say, a Greek Liatiko and a Sonoma Coast Pinot Noir.

That give-and-take between adventure and approachability holds steady across Nur’s drinks program. Mixologist Theo Lieberman, a former colleague of Aubrey’s from Eleven Madison Park, helped create a tidy list of eight Middle Eastern–inflected tweaks on the classics: The Middle Eastern Breakfast is a play on the Bloody Mary, with house-made harissa bringing the heat; the Cardamom Buck is fragrant with the namesake spice. These introduce Adoni’s “exotic” flavors within a familiar frame of reference.

Still, wine represents 60 percent of Nur’s beverage sales. And 60 percent of Nur’s wine is sold by the glass—an eclectic mix that showcases the breadth of the entire list while introducing diners to special finds. Take one of the five reds, Syrocco. It’s from Crozes-Hermitage’s Alain Graillot, but it’s produced in Morocco. It has Syrah’s typical spice, but it’s jammier. Like Adoni’s food, it’s a flavor bomb, priced approachably at $14. It’s a fit for his Damascus qatayef, a fried Syrian pancake stuffed with spiced lamb.

Beyond the wines and cocktails, though, what people in the Middle East drink with mezedhes is arak. Aubrey researched and tasted extensively to collect half a dozen Lebanese and Israeli labels, plus one raki, Turkey’s version of the anise-flavored spirit. His careful curation highlights arak’s surprising range. Smooth and slightly sweet, Chateau Musar’s arak contrasts sharply with the vegetal, floral Ksarak from Chateau Ksara.

For diners unfamiliar with the spirit, Aubrey and his staff offer traditional arak service with dessert. The waiter brings a two-ounce pour in a cut-glass tumbler, adds two parts water to one arak tableside, and drops in an ice cube. From a stickler’s perspective, it might be out of order in the meal, but the ritual fulfills one of Adoni’s goals: to highlight the esprit de coeur of the region.

“It’s Middle Eastern hospitality,” says Aubrey. “I have no problem saying, ‘Hey, try some arak. Let’s take a shot together.’”

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Betsy Andrews is an award-winning journalist and poet. Her latest book is Crowded. Her writing can be found at betsyandrews.contently.com.