I worked as a baker for a number of years, and eventually that work overlapped with my first few wine vintages. I learned more about yeast and fermentation dynamics during my years as a baker than I could have in decades as a winemaker. At the bakery, we worked with up to 20 different fermentations daily—with commercial and native yeasts.

I noticed the impact that different starters and fermentation times had on different breads—those made with native yeast starters had richer aromatics, remarkable depth of flavors, and unique textures. But with wine, you don’t get nearly as many chances to experiment with yeasts—you get one shot a year.

At its most basic level, yeast is what turns grape juice into wine. But because yeast has such a massive potential to influence flavor, choosing the right one is critical to obtain a desired style of wine. I believe that native yeasts play a key role in preserving and expressing the vineyard and regional character of wine—and ultimately increasing the wine’s complexity and quality.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

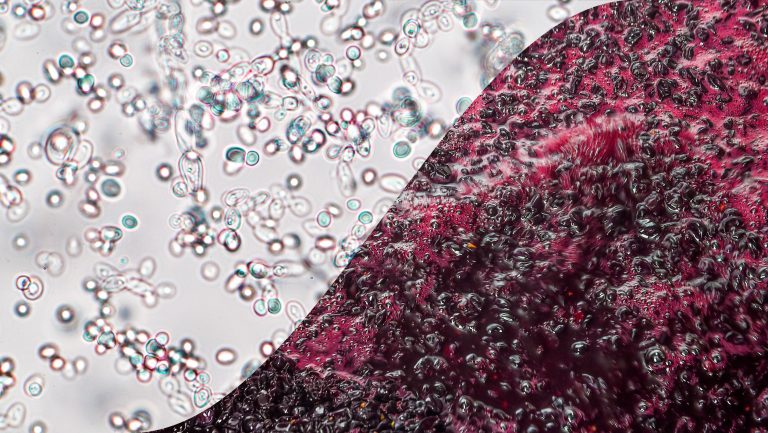

Contrary to the popular belief that commercial Saccharomyces yeasts always take over and finish fermentation because native yeasts cannot, recent lab testing by ETS Laboratories, a leading wine and spirits laboratory headquartered in St. Helena, California, has allowed us to confirm that native yeasts, both Saccharomyces cerevisiae—which can be found native, in the vineyard—and non-Saccharomyces species, are indeed fermenting our wines.

True Terroir Complexity

I met the brothers John and Steve Dragonette, my partners and the cofounders with me of Dragonette Cellars winery in Buellton, California, in the early aughts. We noticed that many New World winemakers were enamored with commercial yeasts, while Old World producers generally favored native yeast fermentations. We relate more to the Old World approach.

In 2005, the year we founded Dragonette, the popular California wine style was bold, ripe, and fruit forward. We thought that native yeasts could help build layers of flavor and texture to increase complexity and, we hoped, show more localized site character.

Since we work with international varieties like Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Grenache, and Syrah, and we age the wines in a combination of new and used French oak barrels, yeast is one of the factors that can really bring a sense of place to our wines. We work with a wide range of vineyards all located over a 30-mile stretch inland from the Pacific Ocean along the Santa Ynez Valley in California.

We ferment each block of every vineyard separately and often make multiple selective passes. In theory, each separate pick should have its own signature yeasts from the microbiome of the vineyard—the community of microorganisms present in a vineyard site—even the individual block. We believe—and ETS Labs analysis backs this up—that yeasts change from year to year as well, and we are fans of really showing the signature of each vintage.

In his book The Science of Wine, the London-based author Jamie Goode writes, “Of the estimated 1,000 or so volatile flavour compounds in wine, at least 400 are produced by yeast.” I was struck by the magnitude of this figure, but it made sense when we looked at our own trials. Aging the wine on the remnant yeast lees—whether native or commercial—plays a continuing role in shaping the flavor components of wine.

At Dragonette, careful selection of clean fruit allows us to age our wine on the lees for up to three years, often without racking. In doing so, we use less sulfur dioxide, as the lees trap and then slowly release carbon dioxide, in turn contributing beautiful texture. Our hope is that the yeasts and lees can take us one step closer to expressing as individual a Santa Barbara terroir as we can.

ETS Findings: Uncommon Yeasts

In 2013 we moved into a winery facility that is all concrete. We pressure-washed the floors and walls before harvest and set out to determine whether native yeasts coming off the vineyard were also finishing our fermentations. To test this theory, we sent samples of our 2016 John Sebastiano Vineyard Syrah to ETS Labs for DNA testing. The lab analyzed different yeast colonies at the beginning, middle, and end of fermentation.

The results confirmed that native yeasts are indeed fermenting our wines. The lab results identified a high level of population diversity without a clearly dominant strain. Native yeasts were active all the way through the ferment, and 10 strains persisted through the whole fermentation process. This is fascinating, given that most native species, like Hanseniaspora uvarum and Pichia fermentans, can ferment only up to 6 to 7% alcohol by volume, while Saccharomyces species, primarily Saccharomyces cerevisiae, whether native or commercial, are capable of fermenting to 12 to 16% ABV or higher.

Expert Insights into Deciphering the Science of Winemaking Yeasts

Discover how wild and commercial strains impact fermentations, as discussed by wine industry professionals

Toward the end of our fermentations, two Saccharomyces strains—similar to the commercial strains Lalvin R2 and CY3079—were identified but together represented only 10 percent of the yeast population. The other 90 percent was made up of native yeast strains not present in the ETS database. We had used Lalvin R2 in the past, so it could have lingered in barrels or on our equipment. The other strain is a yeast we have never used. Rich DeScenzo, the group leader for microbiology at ETS Labs, suggested that it might have come from the previous occupants of the winery, used barrels, or shared equipment, or it might simply have drifted in from a neighboring winery.

In the past, there was an assumption that commercial strains would out-compete native strains because of their high ethanol tolerance, and that commercial strains were always responsible for finishing fermentation. Here again, the results from ETS Labs show that while some commercial strains are present at the end of fermentation, distinct and diverse native strains of Saccharomyces are present as well—suggesting that certain native strains are just as powerful as commercial strains. While commercial strains were present, ETS confirms, and I concur, that our fermentations are being driven by native Saccharomyces strains of yeast.

Most of the time, wineries build up their own microflora, including yeasts and bacteria. DeScenzo has seen wineries—ones that have never used commercial strains—ferment wines solely through populations of native yeasts that exist in the wineries. I asked DeScenzo if ETS has ever found any other yeast beyond Saccharomyces species that can finish a fermentation up to 16% ABV. In eight years of conducting tests, they have not, which is why the evidence of native Saccharomyces yeasts is so important.

Native Neighbors

Interestingly, some of our local winemaker friends are seeing similar results with native yeast fermentations. Husband-and-wife team Amy Christine, MW, and Peter Hunken, the winemakers of The Joy Fantastic in Lompoc, California, feel that cultured commercial yeasts can mask native, natural flavors and aromas. ETS Labs has confirmed that native yeasts from their estate vineyard—a certified organic vineyard planted in the Sta. Rita Hills in 2014—are present throughout their fermentations. “Sense of place is paramount for us,” says Hunken, “and for our new [estate] vineyard, fermenting with native yeast has set the baseline for what our terroir expression is. Some would choose to use commercial strains to enhance a desired element, but we want to capture the vineyard and vintage, and we feel that using native yeasts helps us achieve that goal.”

Mike Roth, the co-owner and winemaker of Lo-Fi Wines in Santa Barbara, is also a proponent of native yeast, but like us, he understands that some wineries use commercial yeasts because of demands of harvest and limited space. “All commercial yeasts were once native,” he says, “but the reality seems to be that all one winemaker can do is their best to make what they consider to be a unique expression of a time and place.”

Cultured yeasts are reliable and predictable and can be selected to achieve specific style goals. But at Dragonette, we aim to coax out discrete local nuances. For us—and for many of our neighbors—using commercial yeast would mean introducing flavors that did not come from our vineyards, therefore eradicating some aspect of the terroir. That’s why we prefer native yeasts, even though they require patience, a bit of faith, and meticulous attention to detail.

While some winemakers take an uncompromising stance toward either commercial or native yeast, ours is a preference. That preference has been informed by our experience that native yeast fermentations tend to show more of a sense of place—a philosophy that is backed by scientific data. We can accurately say that 90 percent of the fermentation tested was the result of native Saccharomyces strains. Now the question is: How do we take it to 100 percent?

—As told to Jonathan Cristaldi

Dispatch

Sign up for our award-winning newsletter

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights—delivered to your inbox every week.

Brandon Sparks-Gillis is a co-owner and vigneron at Dragonette Cellars in the Santa Ynez Valley of Santa Barbara, California, and a Stage 2 Practical Only student in the Master of Wine study program. He attended Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, where he graduated with honors in geology and fell in love with wine.